On March 12, 2020, Ohio Governor Mike DeWine announced the nation’s first statewide closure of K-12 schools due to the emerging threat of COVID-19.[1] What began as a modest, three-week extended spring break to “slow the spread” turned into an entire extra month of students away from in-person instruction,[2] and by May, nearly every state in the nation had announced the closure of their schools through the remainder of the spring semester.[3]

Unfortunately, these final months of the 2019-2020 school year now look less like an unprecedented disruption to K-12 education and more like the modest prologue to a nearly two-year saga of previously unfathomable institutional failure.

Indeed, government guidelines and policies put in place between the spring of 2020 and 2022 not only sacrificed students’ current and long-term well-being, but also unleashed an ill-conceived flood of taxpayer spending ostensibly to address the harms of the pandemic.

While it will take years to fully capture the consequences of these policies, existing data have already begun to reveal several major themes: the prioritization of the union political machine over student well-being, the massive overspending of federal funds, and the costly cycle of fiscal irresponsibility within K-12 that these policies are likely to exacerbate.

Looking in particular at the fiscal stimulus and expenditure patterns of public schools leading up to and during the COVID-19 stimulus period, this report uses Arizona schools as a case study on the failure of government policies to align taxpayer resources with the actual needs of public school students.

Key findings are as follows:

- Keeping with nationwide trends, Arizona school districts triggered a massive statewide enrollment decline of nearly 50,000 students as a result of their COVID mitigation protocols—even as charter school enrollment rose and state and federal taxpayer funding for all public schools surged during the pandemic.

- Arizona school districts spent a significantly smaller proportion of their federal COVID funds (23.6%) than did charter schools (31.3%) during the actual peak of the pandemic (through June 2021), due primarily to the disproportionately high levels of funding that districts have received and accumulated from the federal legislation.

- The vast majority of districts’ expenditures of federal COVID funds in areas such as technology and school facilities upgrades will have occurred more than a full year or more after many public schools successfully reopened for in-person learning, suggesting these funds will primarily serve a non-COVID-related purpose.

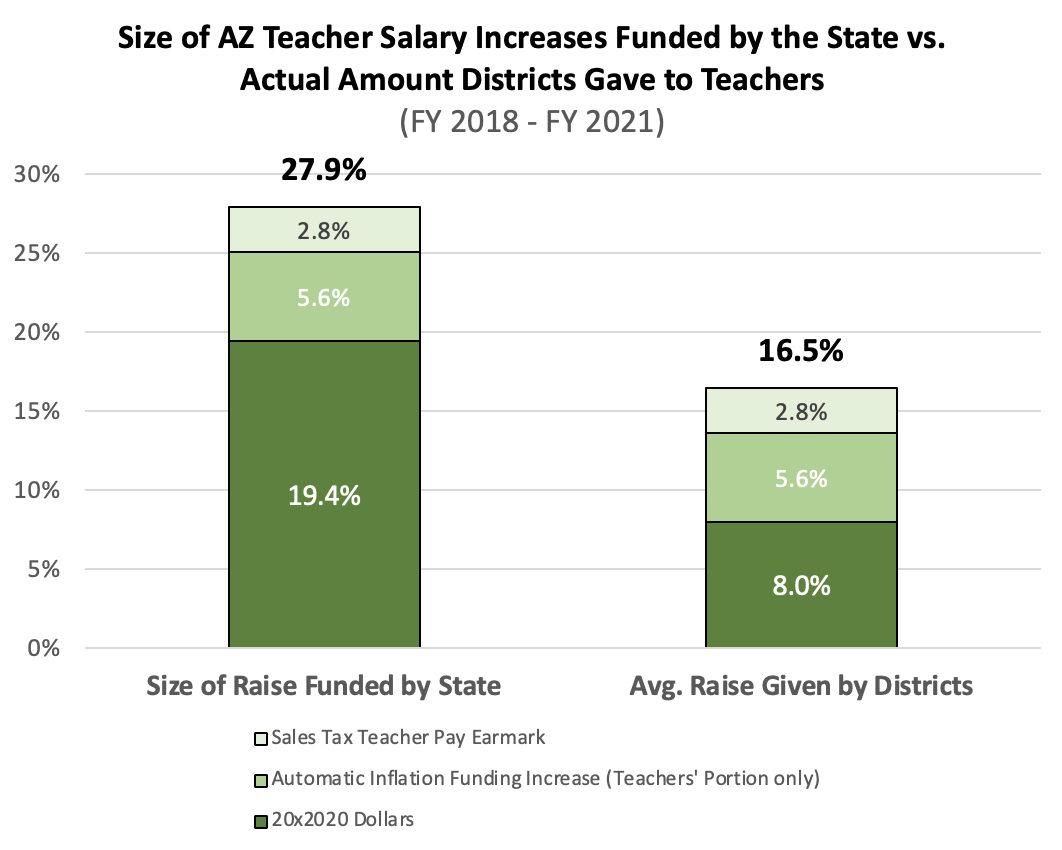

- In the years leading up to and during the COVID-19 pandemic, Arizona district schools provided a 16.5% average teacher pay raise between fiscal years 2018 and 2021, compared to the 27.9% that state lawmakers provided funding for during this time, which points to districts using additional funds to supplant rather than supplement existing revenue streams.

Public School Policies Triggered Enrollment Exodus

As reported by the American Enterprise Institute’s (AEI) “Return 2 Learn Tracker,” 1.2 million K-12 students left public schools across the country between the 2019-2020 and 2020-2021 school years.[4] Yet far from being a universal or unavoidable outcome of the COVID-19 pandemic, this decrease appears directly attributable to the policies enacted by a large share of public schools in response to the pandemic and political pressure. For instance, AEI scholars found that “in Fall 2021, enrollments rebounded in districts that spent 2020-21 mostly in-person. Those that stayed remote longer, saw even more students leave.”[5] (Similar differences in enrollment trends also emerged based upon the prevalence of student masking).

In short, the nation’s aggregate enrollment figures hide an extraordinary divergence between the schools that prioritized a return to normalcy and those that extended disruptions to in-person learning or operated under more draconian COVID protocols.

Such patterns are starkly obvious when looking specifically at Arizona.

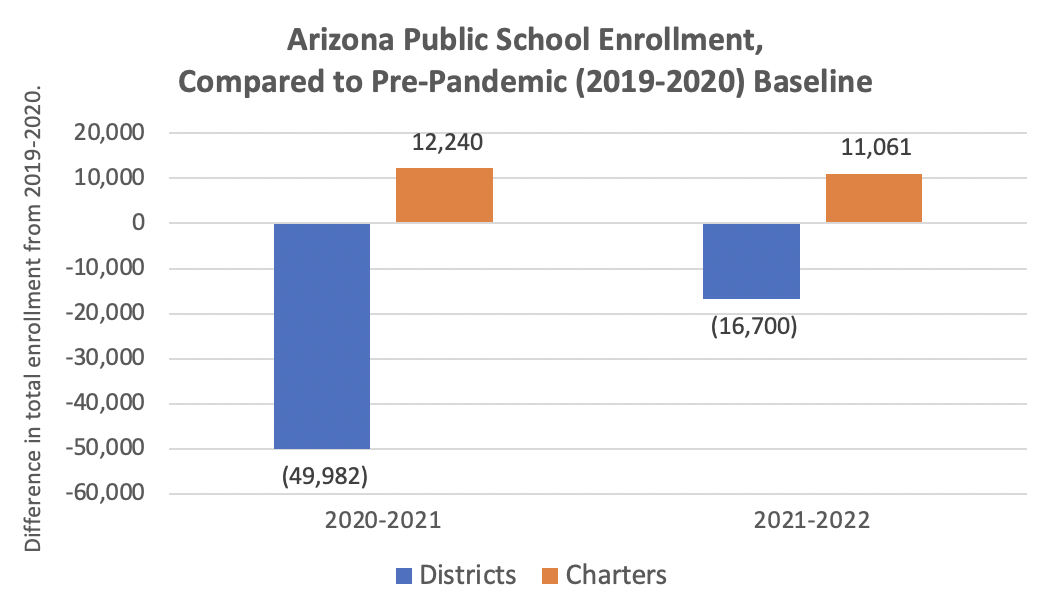

As reported by the state’s Joint Legislative Budget Committee (JLBC), Arizona public school districts shed nearly 50,000 students between the 2019-2020 and the 2020-2021 school years, dropping from 907,121 pupils to 857,139 in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Over those same periods, however, enrollment in Arizona charter schools—which often employed less restrictive COVID measures[6]—increased by over 12,000 students, rising from 208,438 to 220,678.[7] Similar to the differences seen at the national level, this extraordinary difference in enrollment trajectories between the two groups of Arizona schools suggests that differences in schools’ handling of the pandemic significantly drove their enrollment patterns.

Indeed, even as Arizona schools were required to offer at least some in-person instruction beginning in fall 2020 and even as enrollments partially rebounded statewide as shown in Figure 1,[8] traditional public schools remained nearly 17,000 students short of their pre-pandemic levels as of the 2021-2022 school year,[9] with many continuing to employ protocols more aggressively disruptive to student learning—such as class or grade-level quarantines—and mandatory masking requirements.[10]

Figure 1

Source: Arizona Joint Legislative Budget Committee FY 2023 Baseline Book. January 14, 2022, https://www.azjlbc.gov/23baseline/ade.pdf.

Federal COVID Funding

Amid this backdrop of school closures, mask mandates, and enrollment swings, Arizona schools—like those of the nation at large—experienced another seismic force as a consequence of the pandemic: an avalanche of federal funding. Despite its outsize impact on school operations (due to the extensive regulatory requirements placed on states and schools), the federal government’s share of funding for public schools has historically been modest in comparison to state and local contributions, typically making up between 10% to 15% of total funding in Arizona’s K-12 system.[11]

This pattern changed dramatically with the passage of three waves of successively larger federal spending unleashed in response to COVID-19. In the span of a single year, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act of March 2020, the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations (CRRSA) Act of December 2020, and the American Rescue Plan (ARP) of March 2021 together infused nearly $200 billion of federal funding into K-12 education nationwide.[12]

In Arizona alone, public school districts and charter schools were allocated an additional $4.3 billion under these three measures. Compared to the $1.4 billion of federal funding allocated to Arizona public schools in 2019, this extraordinary infusion of funding more than tripled the federal footprint in Arizona’s K-12 system. As a result—even with a significant surge in state and local funding that occurred over this same period—these measures pushed federal dollars up to almost a fourth (24%) of Arizona public school revenues by FY 2022.[13]

Of course, the funds were ostensibly provided as one-time relief to mitigate the harms of COVID-19, not as a permanent increase in ongoing operational school spending. As U.S. News & World Report noted in its June 2020 report “No Way to Reopen Schools Safely Without Federal Bailout:”[14]

Congress has already appropriated $13.5 billion to help stem the financial impact of the coronavirus on K-12 schools, but [Association of School Business Officials Executive Director Daniel] Domenech and other education officials say there’s no way to safely reopen many of them without additional federal resources.

In Arizona alone, public school districts and charter schools were allocated an additional $4.3 billion under these three measures. Compared to the $1.4 billion of federal funding allocated to Arizona public schools in 2019, this extraordinary infusion of funding more than tripled the federal footprint in Arizona’s K-12 system.

Despite such claims, many schools around the country did successfully open less than three months later—before any additional federal appropriations were made. Under Governor Ron DeSantis, for example, Florida schools notably reverted back to in-person instruction beginning in fall 2020,[15] eschewing the massive and prolonged disruption to student learning that other states and school systems continued to impose on their students. The fact that the nation’s third most populous state successfully reopened its schools without waiting months or years for additional federal funding to flow into the state might alone suggest that the subsequent two rounds of federal COVID assistance constituted less a practical necessity than a politically driven windfall. Perhaps even more telling, however, was the messaging from proponents of the expanded funding.

At nearly the same time Florida ordered the reopening of its schools in summer 2020, union organizers throughout other parts of the country not only resisted a prompt return to in-person instruction, but instead—as in the case of the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU)—called for a “massive infusion of federal money to support the reopening” of schools and a laundry list of additional political demands ranging from “police-free schools” to a “moratorium on new charter or voucher programs and standardized testing.”[16]

Calling for a flood of federal funding in the same breath as they issued unrelated political ultimatums, unions like CTU made clear their objectives strayed well beyond solving any actual pandemic-related crisis at hand. Indeed, such activists may have laid bare the political rather than pragmatic roots of efforts to increase federal COVID relief funding when they echoed their peers, as far away as Los Angeles, who similarly demanded the defunding of police and capping of charter schools as part of their summer 2020 COVID reopening platform.[17]

Federal COVID Spending

Given the magnitude of new federal funding for K-12 and the brazenness with which union-affiliated activists had solicited it amid explicitly political demands, it is perhaps unsurprising that the use of these funds has already been called into question nationally. In his 2021 report, “The $200 Billion Question: How Much of Federal COVID-19 Relief Funding for Schools Will Go to COVID-19 Relief,” AEI scholar Nat Malkus observed the following:

Remarkably, Congress placed few limits on what ESSER [COVID K-12] funding can be used for. Although ESSER funds were advertised as supports for school reopenings and pandemic recovery, initial estimates presented in this report suggest that, even with generous assumptions, less than 20 percent of total ESSER district funding will go to reopening, on average, and less than 40 percent will go to recovery. All told, $78 billion–$123 billion, out of nearly $190 billion, could go toward spending not directly related to COVID-19. A majority of these remaining funds will be spent over seven years.

As Malkus further noted, the “expansive permissible uses for ESSER funds raise several questions,” including “whether this overly abundant federal spending was intentional and how an excess of unspent federal funds might affect Democratic ambitions to provide a more permanent federal funding increase to schools through Title I.”[18]

In short, the massive infusion of federal funding for COVID reopening and relief appears to have grossly overshot any realistic targets for either purpose. Rather than more narrowly assisting schools to reopen safely and provide one-time academic recovery, these funds appear to have bankrolled a runway for longer-term spending increases in K-12 across the nation.

Federal COVID Spending in Arizona

In accordance with state reporting requirements enacted by the legislature in 2021, the Arizona Auditor General has compiled COVID spending data for each of Arizona’s public school districts and charter schools. Based on reported expenditures through June 2021 and the planned use of their federal COVID dollars by each district and charter thereafter, the data provide a unique window into the spending patterns of Arizona schools when it come to their federal COVID funds.[19]

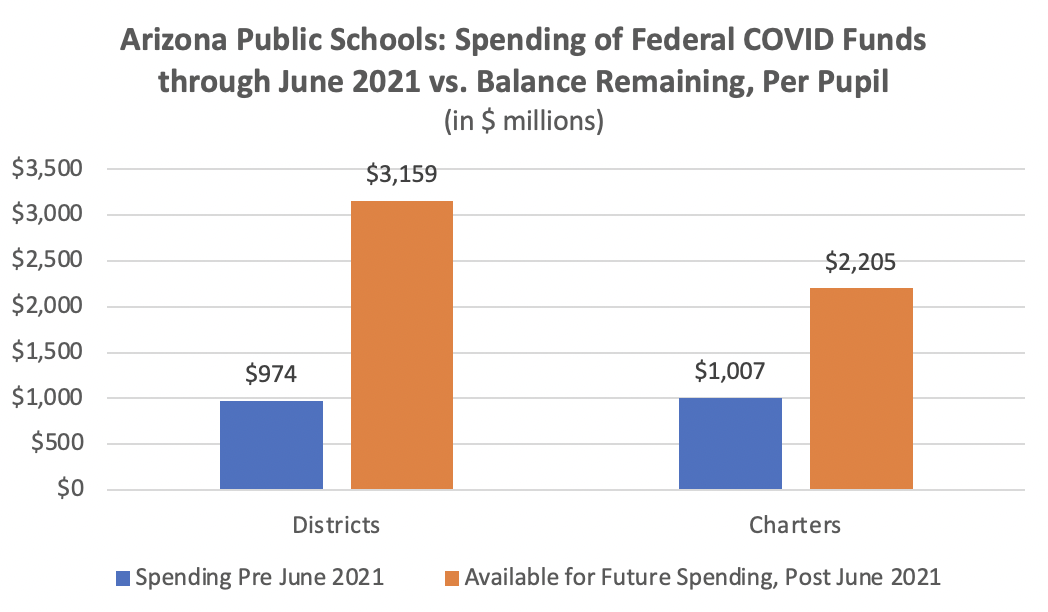

Notably, Arizona public schools spent just $1 billion out of the more than $4 billion of their allocated federal COVID funds by the end of the 2020-2021 school year.[20] That means Arizona public schools spent less than 25% percent of their COVID funds within nine months of schools reopening for in-person learning in Arizona, Florida, and elsewhere, suggesting—as AEI’s Malkus projected nationally—that comparatively little of the federal COVID funding was necessary or even related to safely reopening schools.

Arizona school districts received over $4,100 of federal COVID funds on average,

while charters received just $3,200—or nearly $1,000 less per student than

their district counterparts.

Even this overall rate of spending masks a noticeable difference between the state’s public district schools and public charter schools. Indeed, school districts spent just 23.6% of their total COVID funding by June 2021, while charter schools spent 31.3%.[21]

At first glance, this difference appears to suggest that charters spent their COVID funds faster than district schools, perhaps to facilitate a more robust return to in-person learning. Yet when measured in per pupil terms, charters spent only nominally more than districts by June 2021: $1,007 (charter) vs. $974 (district) per student. The higher proportion of spending by charters over the first year of the pandemic more likely reflects the fact they spent roughly the same amount as district schools out of a far smaller pool of funds.

Indeed, on a per pupil basis, Arizona school districts received over $4,100 of federal COVID funds on average, while charters received just $3,200—or nearly $1,000 less per student than their district counterparts.[22] Thus, despite spending similar amounts per student through June 2021, charter schools exhausted nearly a third of their total COVID funds in that time, while districts used less than a quarter of theirs, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Source: Arizona Joint Legislative Budget Committee FY 2023 Baseline Book. January 14, 2022, https://www.azjlbc.gov/23baseline/ade.pdf.

This disparity in the funding allocations to districts and charters is likewise evident when comparing the share of total federal COVID dollars each received with their enrollment percentages: Arizona districts received $3.6 billion (83.5%) of the state’s total K-12 COVID funding compared to just $710 million (16.5%) for charters, even though charters make up over 20% of actual statewide enrollment.

Given that the majority of these federal COVID funds were allocated using the existing federal Title I formula—which districts typically receive a greater share of—it is little surprise that districts would continue to garner a higher percentage of the new resources. Yet this disproportionate funding for school districts exacerbated underlying disparities that existed before the onset of the coronavirus. As the JLBC has reported, district schools already averaged $1,100 more per pupil in total funding than the state’s charter schools as of FY 2019-2020—prior to the pandemic.[23] This means that additional federal COVID funds nearly doubled the gap between charter and districts, at least in the short term.

Public School Spending Patterns

Arizona district and charter schools may have spent their federal COVID funds in broadly similar amounts through June 2021—even as the latter received substantially less in total than the former—but the actual expenditure patterns of those funds often differ significantly between the two sectors, revealing areas of potentially excessive or misaligned spending.

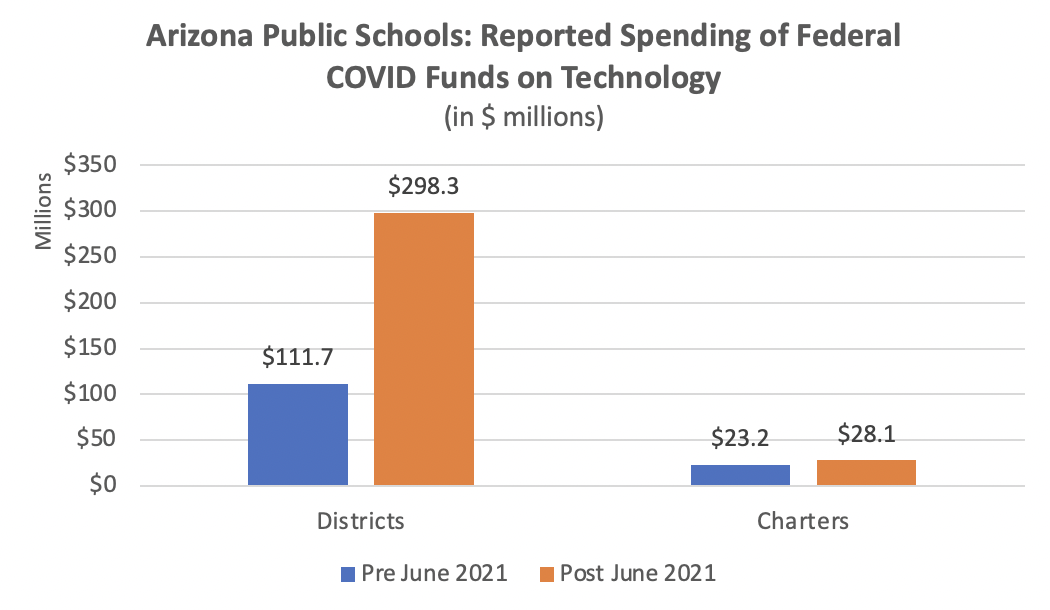

Based on the aggregate amounts reported via the Auditor General, both districts and charters allocated the largest share of their funding toward “maintaining operations and continuity of educational services”—that is, supporting salaries and existing operational costs—with districts expending $456 million and charters $160 million through June 2021. Likewise, both districts and charters reported expenditures on categories such as technology and related hardware in roughly equal proportions, with districts reporting $112 million and charters reporting $23 million through the end of the 2020-2021 school year (merely 3% of their total federal funding).

In other categories and in planned future spending, however, the reported amounts reveal stark differences between district and charter behavior, both in terms of what the schools have already spent, and what they intend to use their COVID funding for going forward.

For instance, while charter schools report planning to spend roughly the same amount again on technology after June 2021 (another $28 million), school districts report plans to nearly triple their spending on technology after June 2021, projecting $298 million in future technology expenditures from the federal COVID funds, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Source: Arizona Auditor General COVID-19 Spending Special Report, 2021, accessed June 25, 2022, https://www.azauditor.gov/District_charter_ADE_COVID-19_spending_special_report.

The similar rates of spending on technology during the 2020-2021 school year suggest that both districts and charters invested their federal COVID funds in computer equipment and software in roughly equal proportions—presumably to help support remote access or hybrid learning options as students oscillated between in-person and at-home learning due to COVID-related quarantines and other disruptions.

However, the massive increase in districts’ spending on technology after June 2021—that is, after COVID vaccines had already become fully available to the more at-risk adult population—suggests that most of the federal COVID relief funding for technology will have simply financed longer-term, structural investments in technology rather than that necessary to cope with the immediate disruptions of COVID protocols when schools were in the deepest throes of the pandemic.

And while it is possible that charters too will have ratcheted up their expenditures on technology well beyond what they projected in 2021, this would simply reinforce the suggestion that the federal COVID funds were predominantly useful for post-COVID needs unrelated to the pandemic.

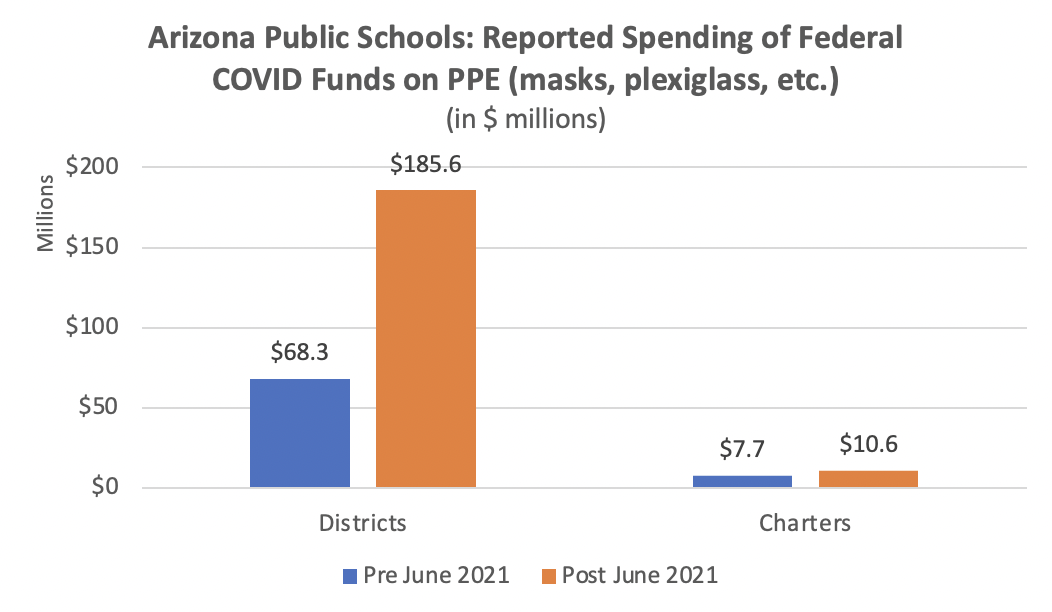

Marked differences arise in districts’ and charters’ spending patterns in other areas as well. When looking at spending on personal protective equipment (PPE)—face masks, plexiglass barriers, additional cleaning services, etc.—districts report spending nearly 10 times as much as charter schools through June 2021: $68.3 million (districts) compared to $7.6 million (charter), and yet districts still planned to more than triple that amount after June 2021, increasing spending on PPE to $185.6 million, even as charters anticipated only a modest increase to $10.6 million.

Given that the PPE category excludes expenditures such as COVID testing and vaccines, this much higher PPE spending suggests that districts invested far more liberally than charters in more visibly conspicuous COVID measures such as masks—and intended to increase that disparity even further after June 2021, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Source: Arizona Auditor General COVID-19 Spending Special Report, 2021, accessed June 25, 2022, https://www.azauditor.gov/District_charter_ADE_COVID-19_spending_special_report.

Indeed, in per pupil terms, districts projected $214 in PPE spending per student after June 2021 compared to $48 per student at charters—a difference equivalent to over $3,000 per teacher per class of 20 students.

In contrast, districts’ and charters’ projected spending totals on “mental and medical health” (which does include COVID testing, etc.) were roughly proportional to the overall share of federal COVID funding each received, with districts forecasting $82 million in post-June 2021 spending, compared to charters’ $14.8 million.

In short, it appears that districts invested significantly higher percentages of their federal COVID funds into certain highly visible mitigation measures—such as masks—than did charters, even as these measures may have had limited if not unintentionally harmful impacts on younger students.[24]

Regardless of their effectiveness, student masking and other COVID protocols were at least intended to mitigate the impact of the coronavirus and thus clearly fall within the original justification of federal COVID spending: providing schools the necessary financial support to implement mitigation strategies and the safe resumption of in-person learning.

Yet other major spending categories of public schools’ COVID-19 funding appear to more clearly stray from the original semblance of pandemic-induced necessity. For instance, the timing and nature of expenditures on “school facilities” further suggest that the bonanza of federal funding given under the guise of COVID safety and recovery represents an historic investment in K-12 schools—but one whose ultimate purpose largely deviates from its original justification.

Through June 2021, Arizona districts and charters invested their federal COVID funds in “school facilities” in similar proportions, with districts recording $27 million and charters $6.9 million. Yet when looking at each sector’s planned expenditures after June 2021, that similarity evaporates. Specifically, while charters projected another $38.3 million in COVID spending on school facilities, districts planned to expend almost 10 times that amount, $347.2 million. (As described above, it is possible that charters too may increase their spending in this or other categories beyond 2021 projections, but the underlying conclusion would still hold: most expenditures of federal COVID funds were made after the point at which they would have been presumably most needed to mitigate the threat of the pandemic.)

The state’s largest public school district, Mesa Unified, projected $75 million of spending from its federal COVID funds on school facility upgrades that would take place after June 2021. Indeed, not until its February 2022 board meeting did the district vote to approve the expenditure of these federal COVID funds on an HVAC upgrade initiative.[25] While ventilation is obviously closely linked to the transmission of the coronavirus, the timing of these expenditures again suggests their value will be chiefly one of post-pandemic benefits to the district. In fact, even local media reported that “[Mesa Assistant Superintendent Scott] Thompson said using the ESSER money on upgraded HVAC was also a way to turn the district’s short-term gain into long-term revenue … by saving about 5% on its energy bill from the upgrades” each year thereafter.[26] While improved energy efficiency may be a laudable and financially prudent goal of the district, such was clearly not the original justification of the COVID stimulus funds.

Finally, while Arizona public schools do project a significant amount of the federal COVID funds will have been used to provide “new programs/curriculum,” including “academic progress assessments, instructional delivery modifications, summer enrichment, after-school programs, etc.” to help students recover from the pandemic, the projected expenditure amounts still appear to offer only a partial justification, at best, of the federal funding. Even with the $533.4 million projected to be spent in total by school districts before and after June 2021 on these types of expenditures—and the corresponding $43.3 million by charters—these figures fall well within the already dismal estimates from AEI’s Malkus when he forecast “less than 40 percent” of federal COVID funds would go to recovery.

The Unnecessary Cost of COVID-19

Perhaps even more important than attempting to quantify what percentage of the federal funding should have gone to schools’ recovery programs, however, is acknowledging why those recovery funds were ostensibly needed in the first place: the unnecessary closure of schools and disruptions to student learning imposed by public health and public education officials. Despite progressive champions and union activists demanding the suspension of in-person instruction throughout the pandemic—including via demonstrations featuring mock coffins, tombstones, and obituaries of teachers in states where conservative lawmakers insisted on reopening schools[27]—research teams at Harvard, Brown, and the Urban Institute concluded that these closure policies may have inflicted up to nearly three times as much learning loss upon students than they would otherwise have faced amid the pandemic, leading even the New York Times to conclude “school closures were what economists call a regressive policy, widening inequality by doing the most harm to groups that were already vulnerable.”[28]

School closures were what economists call a regressive policy, widening inequality by doing the most harm to groups that were already vulnerable.

Moreover, entities such as Georgetown’s Edunomics Lab have not only provided extensive reporting on the use of federal ESSER funds by school districts[29] but also estimated the costs of addressing the learning loss suffered by each district’s students.[30] While the estimated learning losses and corresponding price tags to remedy it are staggering—reaching as high as 22 weeks of lost instruction and an estimated $1.3 billion in remedial education services in places like Los Angeles, according to Edunomics—these statistics both attest to the magnitude of harm caused by government-induced policies.

In other words, the responsibility for these costs—the academic disaster inflicted upon children and the breathtaking financial costs of trying to remedy it—lay almost entirely at the feet of union-led policy decisions that prioritized activist demands over the needs of students.[31] Regrettably, it is now America’s youth who will be left to pay the price of the former, and America’s taxpayers, the price of the latter.

The Redirection of State and Federal Funding: Arizona Case Study:

For all the extraordinary new funding infused into K-12 education by the federal COVID legislation, even that aimed specifically at remediation, historical trends suggest taxpayers and students may get still less than they bargained for. Indeed, looking at recent patterns of Arizona school district spending of state funds leading up to and during the pandemic, there appears to be significant misalignment between state lawmakers’ intentions and school districts’ actual behavior.

Notably, when Arizona Governor Doug Ducey and state legislators approved the “20×2020” teacher raise plan in 2018—to gradually increase average teacher pay statewide by 20% by the 2020-2021 school year, lawmakers entrusted roughly $650 million of additional annual funding to the state’s public school system to boost teacher salaries.[32] Yet, as reported in a prior Goldwater Institute Report The Truth about Teacher Pay in Arizona, school districts had used only a fraction of the available funding increases for teachers as of 2019-2020.

Now that the funding increases from the 20×2020 plan have been fully implemented, it is possible to evaluate how much Arizona districts actually raised teacher salaries during this time in total. Based on its spring 2022 review of Arizona school district spending through the 2020-2021 school year, the state Auditor General concluded that districts had raised average teacher salaries by just 16.5% over the preceding four years, compared to the ostensible 20% target.[33] While this figure alone suggests that districts fell short of state lawmakers’ expectations, it obscures a far deeper disconnect between the schools’ increased funding and the actual use of those funds for expenditures other than their original purpose.

Indeed, while lawmakers provided funding for a 20% teacher pay raise, that funding had been calculated to provide a 20% raise in real, inflation-adjusted terms on top of any other funding increase that teachers would normally receive from their schools.

Over the course of the four years that the 20×2020 teacher pay raise was phased in, school districts also received cumulative inflationary funding increases of 7.0%.[34] Even making an allowance for the share of Arizona teacher salaries not supported by the automatically inflation-adjusted funding formula, this would translate to approximately $2,700 in expected pay raises (or a 5.6% pay bump above where teachers started prior to 20×2020)[35], apart from any increases they should have received from the 20×2020 pay plan.

Moreover, Arizona’s K-12 funding system includes an extra layer of funding generated by a 0.6 cent sales tax add-on applied to nearly all transactions. These funds, which are deposited into the state’s “Classroom Site Fund,” primarily support teacher pay, and the amount of money going into this fund has increased substantially over the past four years as overall sales tax receipts have climbed. Specifically, according to the state’s Joint Legislative Budget Committee (JLBC), between 2017 and 2021, the state’s annual Classroom Site Fund revenues rose over $140 million.[36] On a per-teacher basis, the Auditor General likewise reported $5,840 of funding per teacher in Arizona from the Classroom Site Fund in FY 2017 and $7,215 in FY 2021, for a net increase of nearly $1,400 per teacher.

Taken together, these two sources of additional revenue—the $2,700 from automatic inflationary formula adjustments and the $1,400 of additional teacher pay from the increased sales tax revenues earmarked under the Classroom Site Fund—should have provided Arizona teachers a $4,100 average raise in addition to the funding provided to them by the 20×2020 plan. Compared to the $48,372 average teacher salary at the start of 20×2020, this $4,100 would have represented an 8.5% baseline pay increase.

So districts should have hit not only their 20% target under 20×2020, but also provided an additional 8.5% raise from these other funds. Taken together and making a slight allowance for district versus charter teacher pay, this means teachers should have received cumulative pay raises of roughly 27.9% by the 2020-2021 school year.[37] The 16.5% cumulative raise they actually received amounts to less than two-thirds on average of the funding districts received to increase teacher salaries, as shown in Figure 5. This suggests an enormous substitution effect in which school districts leveraged the extra state funding to supplant their existing funding sources for teachers. In other words, rather than providing the 20×2020 funds on top of the inflation and sales tax-funded increases that teachers could have expected to receive anyway, districts appear to have simply used one as a substitute for the other.

Looked at yet another way, the 16.5% actual raise that districts gave to teachers translated to an increase in average salaries from $48,372 in 2017 to $56,349 in 2021[38]—an increase of $7,977. That means that after accounting for the $4,100 per teacher inflation and sales tax funding increases, districts used their 20×2020 dollars to increase average teacher salaries by just $3,900—far below the roughly $9,400 that districts received in additional funding per teacher for the 20×2020 plan. This disparity equates to districts using just 41% of their 20×2020 funds to increase teacher salaries.

Figure 5

Source: Author’s calculations based on districts’ teacher salary increases as reported in the FY 2021 Auditor General District Spending Report, compared to the overall increase in funding that districts received for teacher compensation via 1) the 20×2020 plan,

2) a proportional share of the automatic state funding increases for base level inflation adjustments in FY 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2021,

and 3) the portion of increased revenues from the Classroom Site Fund that districts applied toward increased teacher salaries in FY 2021 above FY 2017 levels. Subtotals do not add to totals due to rounding.

Because the vast majority of public K-12 funding is fungible, it is perhaps no surprise that Arizona school districts have been able to redirect large swaths of funding intended for one purpose to other areas they believe are more deserving of additional investment. In the case of teacher pay, however, this approach appears to have reinforced a decades-long pattern of school districts dramatically increasing overall expenditures without meaningfully raising teacher salaries in inflation-adjusted terms.[39] Indeed, when even the resources put behind such an ambitious and high-profile teacher pay plan as 20×2020 are so heavily diluted, policymakers should be wary of assurances that other funding initiatives—such as the federal COVID-19 stimulus dollars—will be used as advertised.

It is clear that school districts in Arizona—like those around the country—have found themselves awash in funding from both state and federal coffers in the years leading up to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. But while the aggregate data suggest these funding increases have failed to translate into carefully targeted spending by the districts entrusted with the funds, it is worth looking briefly at certain specific examples of what has taken place.

Example 1: Phoenix Union High School District

The Phoenix Union High School District received $181 million of federal COVID funding, or roughly $6,800 per student enrolled in the district.[40] Not only is the amount substantially higher than districts averaged statewide ($4,200), this surge of funding comes as Phoenix Union’s total per pupil spending already greatly exceeded the statewide average, reaching over $15,000 in FY 2021.[41]

Yet even as the district has received significantly more funding than other districts and has enjoyed an unusually large infusion of federal COVID funds, Phoenix Union’s expenditure patterns suggest a disproportionate amount of its state funding has been directed away from the classroom.

According to the Auditor General, the largest categorical increase in Phoenix Union’s spending over the past five years has been in administration, rising over $500 per student between FY 2020 and FY 2021 alone.[42] During this same 12-month period, the district added eight new principal and assistant principal positions[43],and as of FY 2021, had a student-to-administrator ratio of just 48-to-1, compared to its peer group average of 73-to-1.[44]

As one of the highest-funded districts across the state, Phoenix Union does offer teacher salaries significantly above the statewide average: $62,782 as of FY 2017. Yet amid the massive increases poured into public schools specifically for teacher salaries in recent years, Phoenix Union appears to have routed those funds away from higher teacher pay to an unusually great extent. Indeed, despite receiving roughly $13,500 in extra state funding per pupil for teacher increases (including the roughly $9,400 from the 20×2020 plan, the $1,400 from the Classroom Site Fund sales tax earmark, and $2,700 in inflation adjustments), Phoenix Union increased its average teacher salaries by just $4,300 between FY 2017 and FY 2021.[45]

Example 2: Tucson Unified School District

As another of the largest school districts in the state, Tucson Unified School District (TUSD) also received an exceptionally high allocation of federal COVID funds: $7,200 per student.[46] And like Phoenix Union, its recent spending patterns suggest that the district may also have invested more heavily in maximizing the number of staff on its payrolls than in teacher pay raises over the past several years. According to the Auditor General, TUSD’s average teacher pay failed to significantly increase during the 20×2020 plan, dropping slightly from $50,276 in FY 2017 to $48,487 in FY 2018.

While the district has disputed the Auditor General’s findings,[47] a review of the district’s annual financial reports similarly suggests largely stagnant average teacher salaries over the period.[48] Moreover, given that the district has lost 13% (over 4,000) of its students over the past five years,[49] it appears the district has largely used the additional funds to maintain its workforce to the maximum extent possible rather than consolidating operations or campuses, even as the number of students being served has significantly contracted. The district also now boasts four more assistant superintendent positions than it had in 2017, before the 20×2020 teacher pay raise plan was enacted, including an “Assistant Superintendent of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusiveness.”[50]

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic ushered in an era of unprecedented spending on public K-12 schools, yet available evidence suggests the bonanza of federal spending was almost entirely avoidable and that much of it will likely serve a very different purpose than the one originally sold to policymakers and the public. At the same time, the surge in state level support for K-12 schools in states like Arizona seems also to have increased overall K-12 spending far more than it succeeded in achieving its targeted goals, such as higher teacher salaries.

Policymakers in other states should seek to replicate the steps taken by the Arizona Legislature to mandate reporting requirements on the use of all federal COVID stimulus funds. Given the increasing availability of district-specific spending data in many states from independent analysts such as the Edunomics Lab at Georgetown University, lawmakers across the country will likely have improved access to spending data regardless, but state-specific analyses should take into account both the nature and timing of districts’ expenditure patterns.

Unfortunately, given the political clout of teachers unions in particular, states are likely to witness a repeat of the extravagant funding and spending cycles that have played during the COVID-19 era unless substantial systematic reforms are enacted.

Fortunately in Arizona, policymakers have recently undertaken to do just that, passing in 2022 the nation’s most robust school choice policy in the nation, expanding access to the Empowerment Scholarship Account (ESA) program to every student in the state.[51] Such programs offer to bypass entirely the bureaucracy and middle management of our public education system, putting funds right into the hands of families to ensure any increased investment is passed directly and immediately to the needs of students and by extension —to the educators whom families choose to entrust their children.

End Notes

[1] Office of the Ohio Governor, “Governor DeWine Announces School Closures,” press release, March 12, 2020, https://shakerite.com/campus-and-city/gov-mike-dewine-extends-school-closures-for-rest-of-the-academic-year/20/2020/.

[2] Office of the Ohio Governor, “Governor DeWine Extends School Closure Order,” news release, March 30, 2020, https://shakerite.com/campus-and-city/gov-mike-dewine-extends-school-closures-for-rest-of-the-academic-year/20/2020/.

[3] “The Coronavirus Spring: The Historic Closing of U.S. Schools (A Timeline),” Education Week, July 1, 2020, https://www.edweek.org/leadership/the-coronavirus-spring-the-historic-closing-of-u-s-schools-a-timeline/2020/07.

[4] Return 2 Learn Tracker, American Enterprise Institute, accessed June 25, 2022, https://www.returntolearntracker.net/.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Karla Navarrete. , “Charter School ‘Won’t Mandate a Mask Policy’ as Some Parents Want Options That Don’t Force Masks,.” ABC 15,. July 30, 2020,. https://www.abc15.com/news/getting-back-to-school/charter-school-says-they-wont-mandate-a-mask-policy-as-some-parents-want-options-that-dont-force-mask-use.

[7] FY 2023 Baseline Book: Department of Education, Arizona Joint Legislative Budget Committee, https://www.azjlbc.gov/23baseline/ade.pdf#page=5.

[8] Executive Order 2020-51, “Arizona Open for Learning,” Governor Doug Ducey, July 23, 2020, https://azgovernor.gov/sites/default/files/executive_order_2020-51.pdf.

[9] FY 2023 Baseline Book: Department of Education.

[10] Memorandum, “Re: Students Exposed to COVID-19 in School Districts,” Pima County (Arizona) Administrator’s Office, July 16, 2021, https://webcms.pima.gov/UserFiles/Servers/Server_6/File/Government/Administration/CHHmemosFor%20Web/2021/July/7.16-1.pdf.

[11] K-12 Funding, FY 2013 through FY 2022, Arizona Joint Legislative Budget Committee, August 31, 2021, https://www.azjlbc.gov/units/allfunding.pdf.

[12] Nat Malkus, “The $200 Billion Question: How Much of Federal COVID-19 Relief Funding for Schools Will Go to COVID-19 Relief?” American Enterprise Institute, August 4, 2021, https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/the-200-billion-question-how-much-of-federal-covid-19-relief-funding-for-schools-will-go-to-covid-19-relief/.

[13] Author’s calculations, based on total estimated FY 2022 state and local K-12 revenues ($12,280,239,300) and total estimated state, local, and federal revenues ($16,209,143,500), as reported by the Arizona Joint Legislative Budget Committee, August 31, 2021, https://www.azjlbc.gov/units/allfunding.pdf.

[14] Lauren Camera, “Report: No Way to Reopen Schools Safely Without Federal Bailout,” U.S. News & World Report, June 8, 2020, https://www.usnews.com/news/education-news/articles/2020-06-08/report-schools-need-a-federal-bailout-in-order-to-reopen.

[15] Kate Sullivan, “Florida Gov. DeSantis Says Schools Can Open if Walmart and Home Depot Are Open,” CNN Politics, July 10, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/07/10/politics/florida-desantis-walmart-home-depot-schools-reopen/index.html.

[16] CTU Communications, “Taking Matters Into Our Own Hands,” Chicago Teachers Union, October 13, 2020, https://www.ctulocal1.org/chicago-union-teacher/2020/10/taking-matters-into-our-own-hands/.

[17] Zachary Evans, “L.A. Teachers Union Calls to Defund Police, Cap Charter Schools as Part of COVID Reopening Plan,” National Review, July 16, 2020, https://www.nationalreview.com/news/l-a-teachers-union-calls-to-defund-police-cap-charter-schools-as-part-of-covid-reopening-plan/.

[18] Malkus, The $200 Billion Question.

[19] Arizona Auditor General, “District, Charter, and ADE COVID-19 Spending Special Report,” accessed June 25, 2022, https://www.azauditor.gov/District_charter_ADE_COVID-19_spending_special_report.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Author’s calculations based on Arizona Auditor General, COVID-19 Special Report.

[22] Arizona Auditor General, COVID-19 Special Report.

[23] Overview of K-12 Per Pupil Funding for School Districts and Charter Schools, Arizona Joint Legislative Budget Committee,

August 23, 2021, https://www.azjlbc.gov/units/districtvscharterfunding.pdf.

[24] David Leonhardt, “Why Masks Work, but Mandates Haven’t,” New York Times, May 31, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/31/briefing/masks-mandates-us-covid.html; David Zweig, “The CDC’s Flawed Case for Wearing Masks in School,” The Atlantic, December 16, 2021, https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2021/12/mask-guidelines-cdc-walensky/621035/; Anya Kamenetz, Anya Kamenetz, “After 2 Years, Growing Calls to Take Masks off Children in School,” NPR, January 28, 2022, https://www.npr.org/2022/01/28/1075842341/growing-calls-to-take-masks-off-children-in-school.

[25] Governing Board Meeting, Mesa Public Schools, February 22, 2022, https://go.boarddocs.com/az/mpsaz/Board.nsf/files/CBNT7Z760C65/$file/19F-0904%20Board%20Increase%20JOC%20HVAC%2002-08-2022.pdf.

[26] Scott Shumaker, “Cooler Classrooms at Less Cost in Store for MPS,” East Valley Tribune, February 27, 2022, https://www.eastvalleytribune.com/news/cooler-classrooms-at-less-cost-in-store-for-mps/article_14a96432-9726-11ec-ac68-1369c432cec9.html.

[27] Matt Beienburg. “How the Education Establishment Botched COVID-19 and Boosted the School Choice Movement,” Discourse, April 11, 2022, https://www.discoursemagazine.com/politics/2022/04/11/how-the-education-establishment-botched-covid-19-and-boosted-the-school-choice-movement/.

[28] David Leonhardt, “Not Good for Learning,” New York Times, May 5, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/05/briefing/school-closures-covid-learning-loss.html.

[29] ESSER Expenditure Dashboard, Edunomics Lab, Georgetown University, accessed June 25, 2022, https://edunomicslab.org/esser-spending/.

[30] “Calculating Investments to Remedy Learning Loss,” Edunomics Lab, Georgetown University, accessed June 25, 2022, https://edunomicslab.org/calculator/.

[31] Susan Ferrechio, “Teachers Unions Worked with CDC to Keep Schools Closed for COVID, GOP Report Says,” Washington Times, March 30, 2022, https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2022/mar/30/republican-report-shows-teachers-unions-helped-cdc/.

[32] Background on Teacher Pay Raise Calculations, Arizona Joint Legislative Budget Committee, May 18, 2018, https://www.azleg.gov/jlbc/teacherpayraisecalc.pdf.

[33] School District Spending Analysis—Fiscal Year 2021, Arizona Auditor General, accessed June 25, 2022, https://sdspending.azauditor.gov/?year=2021.

[34] The Arizona Joint Legislative Budget Committee FY 18 – FY 21 Appropriations Reports record that public schools received base level inflation adjustments of 1.31% in FY 2018, 1.8% in FY 2019, 2.0% in FY 2020, and 1.74% in FY 2021 for a cumulative increase of approximately 7.0%. https://www.azleg.gov/jlbc/18AR/ade.pdf; https://www.azleg.gov/jlbc/19AR/ade.pdf ; https://www.azleg.gov/jlbc/20AR/ade.pdf; https://www.azleg.gov/jlbc/21AR/ade.pdf.

[35] Based on JLBC data, approximately 80% of teacher salaries are supported by the base level, with the remainder funded by the Classroom Site Fund, federal funds, and other sources. Therefore, approximately 80% of the $48,372 FY 2017 average teacher salary was subject to the 7.0% inflation funding allowance, resulting in an average increase in funding for teacher salaries during this period of $2,719. See “The Truth About Teacher Pay in Arizona” for more information: https://www.goldwaterinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/teacher-pay-FINAL-5-12-21.pdf.

[36] JLBC, K-12 Funding, FY 2013 Through FY 2022.

[37] Actual increase in funds for districts adjusted downward by 2.8% to reflect lower average charter school teacher salary costs, according to the JLBC staff report “Background on Teacher Pay Raise Calculations”: https://www.azleg.gov/jlbc/teacherpayraisecalc.pdf.

[38] School District Spending Analysis—Fiscal Year 2021. Arizona Auditor General.

[39] Matt Beienburg, “A History of Increase: K-12 Funding in Arizona,” Goldwater Institute, October 16, 2020, https://www.goldwaterinstitute.org/az-k12funding.

[40] District, Charter, and ADE COVID-19 Spending Special Report, Arizona Auditor General.

[41] School District Spending Analysis—Fiscal Year 2021: Phoenix Union High School District, Arizona Auditor General, accessed June 25, 2022, https://sdspending.azauditor.gov/District/DistrictPage?year=2021&ctd=070510.

[42] Ibid.

[43] School District Employee Report: Phoenix Union High School District, Arizona Department of Education, FY 2020 and FY 2021, accessed June 25, 2022, https://www.ade.az.gov/sder/PublicReports.asp?FiscalYear=2020; https://www.ade.az.gov/sder/PublicReports.asp?FiscalYear=2021.

[44] School District Spending Analysis—Fiscal Year 2021: Phoenix Union High School District, Arizona Auditor General.

[45] School District Spending Analysis—Fiscal Year 2021 Data File, Arizona Auditor General, https://sdspending.azauditor.gov/data/AZ_School_District_Spending_FY21_Data_File.xlsx.

[46] District, Charter, and ADE COVID-19 Spending Special Report, Arizona Auditor General.

[47] Genesis Lara, “TUSD Says its Teacher Pay Raises Were Higher than Auditor Reported,” Arizona Daily Star, May 20, 2022, accessed June 25, 2022, https://tucson.com/news/local/education/tusd-says-its-teachers-pay-raises-were-higher-than-auditor-reported/article_48a5586a-a16f-11ec-9b6a-4fd004ea0ee5.html.

[48] FY 2017 and FY 2021 Superintendent’s Annual Financial Reports, Arizona Department of Education, https://www.azed.gov/sites/default/files/2022/03/SAFR2021vol2.pdf; https://www.azed.gov/finance/files/2018/01/2017SAFR.zip.

[49] Arizona Auditor General District Spending Analysis—Fiscal Year 2021 Data File.

[50] Equity, Diversity, and Inclusiveness Department, Tucson Unified School District, accessed June 25, 2022, http://tusd1.org/Departments/Equity-Diversity-Inclusiveness.

[51] HB 2853, Arizona House of Representatives, Fifty-Fifth Legislature, Second Regular Session, 2022, https://www.azleg.gov/legtext/55leg/2R/bills/HB2853H.pdf.