Introduction

Americans’ civic memory is fading. The share of adults who can name even the fundamental rights of the First Amendment has dropped by as much as half in recent years, while the percentage who are “extremely/very proud to be an American” has fallen from over 90 percent in 2004 to just 67 percent in 2024.[1]

Yet rather than renewing civic literacy and enthusiasm among the rising generations, many instructional programs and school resources are actively compounding the erosion of confidence in our constitutional republic. As a result, it is now more important than ever that parents and educators be equipped with the tools to teach our students an engaging, factually robust account of American history and government.

As a service to parents, school board members, and educators, the Van Sittert Center for Constitutional Advocacy has assembled a comparison of two of the most ambitious and prominent literary projects ever undertaken to teach high school-aged children the history of the United States of America: Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United Statesand Wilfred McClay’s Land of Hope: An Invitation to the Great American Story.

Authored by a self-described “democratic socialist” who “believe[s] in the wiping out of national boundaries,”[2] Zinn’s work has sold more than 2 million copies since its first publication in 1980.[3] In conjunction with the affiliated online Zinn Education Project, its narrative informs the instruction provided to students in as many as 1 in 4 public school history classrooms across the country.[4]

In turn, Wilfred McClay published Land of Hope nearly 40 years after the original printing of Zinn’s tome, drawing on his career as a faculty historian who has taught at the University of Oklahoma, Georgetown, Johns Hopkins, Hillsdale, and Tulane.[5]

Both Zinn’s and McClay’s works share with students across the country an expansive account of their nation’s history. Yet beyond the shared goal of transmitting historical awareness to current and future generations of students, these two works diverge enormously in their approach and in the aspirations of their authors.

As McClay declares at the outset, his intent is to “offer to American readers, young and old alike, an accurate, responsible, coherent, persuasive, and inspiring narrative account of their own country.”[6]

Zinn, in contrast, has described outside the pages of A People’s History his own historical perspective on the nation’s story in starkly different terms:

From that moment on, I was no longer a liberal, a believer in the self-correcting character of American democracy. I was a radical, believing that something fundamental was wrong in this country … something rotten to the root.[7]

Indeed, building off his antipathy toward classical liberal government, Zinn elsewhere describes other influences on his historical perspective, noting for instance, “Marx’s Communist Manifesto was … immensely useful and inspiring.”[8]

Given the dramatically different perspectives of these two authors and the extent to which schools incorporate their materials into U.S. history instruction, it is critical that parents and educators alike explore the offerings presented to their children.

In the following pages, parents, teachers, and school leaders will find a direct comparison of passages from both Zinn and McClay illustrating how each covers important eras of American history, specifically:

- The Revolutionary War and the founding of the United States

- The irrepressible conflict over slavery and the Civil War

- The close of World War II, and the Cold War against the communist regime of the USSR

- The Civil Rights Movement

While many are familiar with Zinn’s work—at least in the abstract, if not the particular passages—rarely is the contrast between two fundamentally different narratives of the American experiment so neatly delineated as in the comparison of Zinn’s and McClay’s foundational texts. This report provides merely a few snapshots of the competing versions of American history told through each work. But as the following pages demonstrate, these differing accounts are likely to leave students either inspired or embittered in their attitudes toward the United States, depending on which text they receive. Depending on the book chosen, students will be predominantly presented with:

- A belief that the American Revolution was a project of economic manipulation and political oppression perpetrated by wealthy elites at the expense of the poor (Zinn), or a historically unprecedented advancement in declaring and securing liberty, equality, and self-determination advanced by flawed but extraordinary figures (McClay).

- A resentment toward Abraham Lincoln and the people of Northern states during the Civil War for insufficient opposition to the institution of slavery (Zinn), or an appreciation for the extraordinary arc of history advanced by abolitionist leaders against anti-capitalist apologists of slavery (McClay).

- A sense of moral equivalence between the United States and USSR and a condescension toward those opposed to the spread of communism under the USSR (Zinn), or a sober assessment of the threat, duplicity, and illiberal designs of the communist totalitarian regime, even while acknowledging the excesses of McCarthyism (McClay).

- A belief that civil rights reforms have amounted to little more than window dressing amid a backdrop of ongoing, intractable systemic oppression (Zinn), or a veneration of the progress won by heroes of the Civil Rights Movement to further advance the promises of the Declaration of Independence and ensure equality before the law for members of all races (McClay).

Taken together, such contrasts encapsulate and mirror much of the nation’s current divide in civic and political dialogue. Indeed, the adoption of one text versus the other will likely help determine which narrative about the American republican experiment future generations will adopt.

The Founding Era

Understanding the American founding is critical not only to students’ academic knowledge, but to their civic awareness and participation. Therefore, it is worthwhile to compare how Zinn and McClay portray the actors involved and the potential takeaways for students reading each of these books. While McClay presents in generally high esteem the founding generation (even as he criticizes their failings), Zinn casts aspersions on both the underlying motivations of the revolution and on virtually every venerated figure from the time.

Beginning with Zinn’s A People’s History, the first of its chapters on the subject of the revolutionary period is titled “Tyranny Is Tyranny,” in which he argues that the grievances held against colonial governments and the British parliament were rooted in the same cause—that the poor were oppressed by the wealthy—but the wealthy on the American continent found a way to harness the energy of the poor into a weapon against the wealthy of Europe. Specifically, he writes:

[Colonial elites] found that by creating a nation, a symbol, a legal unity called the United States, they could take over land, profits, and political power from favorites of the British Empire. In the process, they could hold back a number of potential rebellions and create a consensus of popular support for the rule of a new, privileged leadership. (Zinn, p. 59).

Here and elsewhere, this chapter helps introduce one of Zinn’s most recurring themes—the idea of ever-present economic exploitation as an explanation of events. In this chapter, Zinn removes moral principles, dispenses with legal rights, and scrubs free any sense of agency among 18th century American colonists and replaces it with a flattened sense of greed and self-interest.

Contrast this with McClay, who credits the colonists with cultivating and cherishing “the habit of self-rule.” According to McClay, this attribute was something “they were not likely ever to want to give up easily or willingly.” Indeed, McClay credits the revolution to a confluence of higher ideals:

Beneath all the particular points of conflict between England and America were fixed and sharply divergent ideas: about the proper place of America in the emerging imperial system, about the meaning of words like self-rule, representation, constitution, and sovereignty. (McClay, p. 45)

Zinn, on the other hand, suggests to students that the discussion of principles, rights and sovereignty offers little more than a facade covering hidden purposes. Speaking of the resistance that broke out against British rule in the form of boycotts, protests, and eventually open conflict, for example, Zinn writes:

We have here a forecast of the long history of American politics, the mobilization of lower-class energy by upper-class politicians, for their own purposes. (Zinn, p. 61)

In essence, Zinn argues that the volunteers who became minutemen, the households that refused to buy British tea, the printers who flaunted the Stamp Act, and the jurors who ignored the crown-appointed judges and acquitted their fellow citizens were duped by ambitious politicians into fighting for a new system of oppression. Cementing this perspective, Zinn writes further:

When we look at the American Revolution this way, it was a work of genius, and the Founding Fathers deserve the awed tribute they have received over the centuries. They created the most effective system of national control devised in modern times, and showed future generations of leaders the advantages of combining paternalism with command. (Zinn, p. 59)

Besides offering an extraordinarily dim view of the revolution, such an argument badly distorts the aims of those who undertook it. Indeed, Zinn’s assertion that the colonists sought to devise unprecedented levels of control over the American people are refuted virtually instantly by their own first attempt at forging a new government under the Articles of Confederation. That agreement simply could not advance a paternalistic and commanding government, as it famously created a federal government so weak that it could not sustain even itself. The subsequent Constitution likewise was actively designed to stymie the impulses of control and paternalism by those in power—reiterating in the 10th Amendment, for example, that the powers not specifically given to the national government were to be reserved to the people and to the states. Indeed, the Constitution was formulated with an explicit bias against the powers of the national government, even as it fixed specific weaknesses of the Articles (most notably the inability to enforce its own laws).

In sharp contrast to Zinn’s disapproval of the new American system of government, McClay notes:

There is only one nation on earth that can point with pride to a written Constitution that is more than 230 years old, a continuously authoritative expression of fundamental law that stands at the very center of our national life. (McClay, p. 69).

As McClay goes on:

Our Constitution accepted the inevitability of our diversity … and the inevitability of conflicts arising out of our differences. … It recognized the fact that ambitious, covetous, and power-hungry individuals are always going to be plentifully in evidence among us and that the energies of such potentially dangerous people need to be contained and tamed, diverted into activities that are consonant with the public good. (McClay, p. 69).

Such passages further highlight the chasm between McClay and Zinn’s narratives of America’s birth: while Zinn presents the Constitution as a tool of exploitation and control, McClay celebrates its drafting as an extraordinary achievement that would go on to protect Americans’ liberties for centuries into the future.

Unfortunately, this split between the two authors extends even to other pillars of the American experiment. Specifically, Zinn’s condescension for the founding era extends even to the Declaration of Independence. His maximalist view of egalitarianism leads him to decry the document and the founding, for example, for not immediately producing equal outcomes among disparate groups. As he declares:

The Declaration, like Locke’s Second Treatise, talked about government and political rights, but ignored the existing inequalities in property. And how could people truly have equal rights, with stark differences in wealth? (Zinn, p. 73)

Setting aside the fact that this is not historical analysis but rather offered as a rhetorical question, it is worth recognizing that Zinn stalwartly refuses to acknowledge the extreme value of political and legal rights. Again the agenda is clear; rather than recognizing the ideals of the Declaration as an unprecedented advancement in human civilization and reference point to pursue greater liberty for greater numbers of people, Zinn tells students that the foundation of the nation was false, if not rotten to its core—presumably to entice their support for replacing it entirely.

McClay, in contrast, handles the contradictions of the founders, who believed in equality conceptually but had not entirely grappled with its implications. Acknowledging the many ways to interpret the principles espoused in the Declaration, McClay ends his chapter on the Revolution in this way:

But all these questions lay in the future, and answering them would be one of the principal tasks facing the new nation for the next 250 years. The Revolution was prosecuted by imperfect individuals who had a mixture of motives, including the purely economic motives of businessmen who did not want to pay taxes and the political conflicts among the competing social classes in the colonies themselves. Yet self-rule was at the heart of it all. Self-rule had been the basis for the flourishing of these colonies; self-rule was the basis for their revolution; self-rule continued to be a central element in the American experiment in all the years to come. (McClay, p. 50)

Students reading McClay are left with an appreciation of the complexities and messiness of America’s founding, but also an understanding that it established a historically unprecedented system of governance based on enduring ideals that they themselves can help see flourish even today.

Slavery, Civil War, and Reconstruction

As with their accounts of America’s founding overall, Zinn and McClay relate the history of slavery in the United States in radically different ways, and to dramatically different effect upon readers.

As McClay notes, the founders’ created a system of government that

fell short, and grievously so, in one important respect: its failure to address satisfactorily the growing national stain of slavery. As we will see, there were understandable reasons for that failure. But the trajectory of history that was coming would not forget it, and would not forgive it. (McClay, p. 70).

Indeed, as McClay describes even of the revolutionary period itself:

There was real bite to the mocking question fired at the Americans in 1775 by the British writer Samuel Johnson: “How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of the negroes?” It was an excellent question. (McClay, p. 71).

Yet even as McClay unabashedly forces readers to confront the stain and sin of slavery and the participation in the institution by many of new nation’s framers, he likewise rejects more modern revisionist narratives that seek to portray slavery as America’s—rather than mankind’s—sin, noting:

Slavery is as old as human history. It has existed on all habitable continents. … In the New World, its introduction was pioneered by the Portuguese and Spanish, beginning in the sixteenth century. (McClay, p. 70).

Rather than blithely excusing or uniquely condemning the founding generation, McClay encourages readers to wrestle with their moment in history:

How, we wonder today, could otherwise enlightened and exemplary individuals have been so blind to the fundamental humanity of those they confined? How could they have made their peace with practices so utterly contradictory to all they stood for? There is no easy answer to such questions. But surely a part of the answer is that each of us is born into a world that we did not make, and it is only with the greatest effort, and often at very great cost, that we are ever able to change that world for the better. (McClay, p. 71).

McClay proceeds to offer not only a rich account of the founders’ feats and failures on this issue, but carefully explores the political constraints at play during the time of drafting the Constitution. As he notes:

The price of pursuing abolition of slavery at that time would almost certainly have been the dissolution of the American nation. … The ambivalences regarding slavery that had been built into the structure of the Constitution were almost certainly unavoidable in the short term in order to achieve an effective political union of the nation. What we need to understand is how the original compromise no longer became acceptable to increasing numbers of Americans, especially in one part of the Union, and why slavery, a ubiquitous institution in human history, came to be seen not merely as an unfortunate evil but as a sinful impediment to human progress, a stain upon the whole nation. (McClay, p. 73)

Perhaps most significantly, McClay summarizes:

It would be profoundly wrong to contend, as some do, that the United States was “founded on” slavery. No, it was founded on other principles entirely, on principles of liberty and self-rule that had been discovered and defined and refined and enshrined through the tempering effects of several turbulent centuries of European and British and American History. (McClay, p. 73)

In contrast, rather than celebrating the Constitution as an advancement toward securing human liberty and equality unmatched anywhere on the globe—even if incomplete in its reach—Zinn simply condemns it as if it were the cause and justification for evils such as slavery. He writes, for example:

The inferior position of blacks, the exclusion of Indians from the new society, the establishment of supremacy for the rich and powerful in the new nation—all this was already settled in the colonies by the time of the Revolution. With the English out of the way, it could now be put on paper, solidified, regularized, made legitimate, by the Constitution of the United States, drafted at a convention of Revolutionary leaders in Philadelphia. (Zinn, p. 89).

Indeed, in Zinn’s telling, the Constitution is uniquely responsible for legitimizing slavery, even as its framers had scrupulously crafted the document to avoid even recognizing the terms “slave,” “slavery,” “master,” or “owner,” and even as many of the framers expected slavery to die out.[9].

Moreover, while Zinn appears eager in this passage to condemn the new nation for its failure to extend immediate, total equality to all persons, it falls yet again to McClay to fill in the gaps left by A People’s History when it comes to the record of the colonists:

Of course, citizenship and the ability to participate in the political process in these colonies were severely restricted when measured by our present-day standards, since women, Native Americans, and African Americans were not permitted a role in colonial political life. But it is important to keep that fact in correct perspective. Such equality as we insist upon today did not then exist anyplace in the world. That said, no other region on earth had such a high proportion of its adult male population enjoying a free status rooted in the private ownership of land. (McClay, p. 34)

In short, while McClay makes no attempt to shield students from the horrors and hypocrisies of slavery—nor deny the unequal treatment endured by many of the groups living within the new American nation—he ensures that students are not left cheated of the surrounding historical backdrop as they are with Zinn.

Similarly, though Zinn recognizes the 1808 Congressional action to ban the importation of slaves to the United States and acknowledges that even some prominent Southerners—Thomas Jefferson most famously—had written disapprovingly of slavery even while being slaveowners, he suggests such statements merely concealed ulterior motives. As he declares, for instance:

Thomas Jefferson had written a paragraph of the Declaration accusing the King of transporting slaves from Africa to the colonies and “suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or to restrain this execrable commerce.” This seemed to express moral indignation against slavery and the slave trade. … [But] behind it was the growing fear among Virginians and some other southerners about the growing number of black slaves in the colonies … and the threat of slave revolts as the number of slaves increased. (Zinn, p. 72)

Zinn’s tendency to thus ascribe only the most underhanded motivations to figures like Jefferson is mirrored in his account of subsequent generations as well. In particular, his narrative of those on the stage leading up to and during the Civil War again reverts to a combination of condescension and economic resentment toward virtually all involved:

Behind the secession of the South from the Union, after Lincoln was elected President in the fall of 1860 as candidate of the new Republican party, was a long series of policy clashes between South and North. The clash was not over slavery as a moral institution—most northerners did not care enough about slavery to make sacrifices for it, certainly not the sacrifice of war. It was not a clash of peoples (most northern whites were not economically favored, not politically powerful; most southern whites were poor farmers, not decisionmakers) but of elites. The northern elite wanted economic expansion—free land, free labor, a free market, a high protective tariff for manufacturers, a bank of the United States. The slave interests opposed all that; they saw Lincoln and the Republicans as making continuation of their pleasant and prosperous way of life impossible in the future. (Zinn, p. 189).

Ironically, this insinuation from Zinn—that the North transgressed upon the South for the purpose of “economic expansion”—echoes the narrative promoted by the infamous pro-slavery fanatic George Fitzhugh. McClay, in contrast, actively criticizes Fitzhugh’s radical view of the slavery and the North:

In the view of the Virginian George Fitzhugh, one of the more influential of the pro-slavery apologists in the 1850s, the paternalism of slavery was far preferable to the “wage slavery” of northern industrial society, in which greedy, profit-oriented capitalists took no responsibility for the comprehensive well-being of their workers but instead exploited them freely and then cast them aside like used tissues when their labor was no longer useful. (McClay, p. 149)

As McClay notes further:

Fitzhugh argued not only against capitalism but against the entire liberal tradition, including the ideas of such foundational thinkers as Locke and Jefferson, countering that free labor and free markets and other individual liberties only served to enrich the strong while crushing the weak. “Slavery,” he wrote, “is a form, and the very best form, of socialism,” the best counter to the rampant competitiveness and atomization of “free” societies. With Fitzhugh, we have come a very long way from the ideals of the American Founders. (McClay, p. 149)

In short, McClay highlights the fact that the very same supporters of slavery such as Fitzhugh were themselves (like Zinn) fierce critics of free market capitalism and the classical liberal tradition underpinning the Constitution. Indeed, whether Fitzhugh or Zinn, such self-avowed proponents of “socialism” appear united in their disdain for the Civil War-era North.

Far more significant than McClay or Zinn’s respective treatment of figures like Fitzhugh, however, remains their treatment of the motivations of Lincoln and the North overall. Like Zinn, McClay recognizes that Lincoln did not enter the war initially as a moral crusade against slavery, but unlike Zinn, he does not manufacture a narrative of economic opportunism as Lincoln’s rationale. Rather, McClay notes Lincoln’s unwavering commitment to the preservation of the Union and Constitution:

Lincoln … saw secession as a form of sheer anarchy, one that, by refusing to accept the results of a legitimate election, would serve to subvert and discredit the very idea of democracy itself in the eyes of monarchists and aristocrats around the world.” (McClay, p. 173)

Zinn, on the other hand, speaks even further of the North’s motivations in openly contemptuous terms:

Such a national government would never accept an end to slavery by rebellion. It would end slavery only under conditions controlled by whites, and only when required by the political and economic needs of the business elite of the North. (Zinn, p. 187)

Students reading McClay are thus left to appreciate the tensions, complexities, and motivations of that period in a way wholly different from the unapologetic disdain offered by Zinn. The commitment and sacrifices of those who sought to preserve the American experiment and contain or eliminate slavery are generally honored in McClay’s telling rather than too often trivialized by Zinn.

World War II and The Cold War

An increasing number of states, including Florida and Arizona, have enacted legislation requiring that students be taught a “comparative discussion of political ideologies, such as communism and totalitarianism, that conflict with the freedom and democracy that are essential to the founding principles of the United States.”[10] Some of the work toward achieving that goal is easily done when U.S. history courses teach the Cold War, as it provides a backdrop for analyzing the key features of American democracy in comparison with Soviet communism.

Reading A People’s History, however, gives students a skewed perspective on why the U.S. was locked into a decades-long conflict with the Soviet Union. In fact, even before introducing students to the Cold War itself, Zinn first portrays the United States as having engaged in nuclear aggression for almost unfathomably immoral purposes in World War II:

The dropping of the second bomb on Nagasaki seems to have been scheduled in advance, and no one has ever been able to explain why it was dropped. Was it because this was a plutonium bomb whereas the Hiroshima bomb was a uranium bomb? Were the dead and irradiated of Nagasaki victims of a scientific experiment? (Zinn, p. 424).

Questioning likewise the Americans’ justification for using the bomb in the first place, Zinn asks:

Was it because too much money and effort had been invested in the atomic bomb not to drop it? (Zinn, p. 423).

Such quasi-conspiratorial musings stand in stark contrast to McClay’s text, which contemplates the realities facing the United States’ decision to first use the atomic bomb. Writing of the Pacific theater in World War II, McClay does not shy away from the horrific destruction and loss of life unleashed by the bombs, but neither does he simply gloss over the considerations of that moment:

Victory … was going to involve a range of horrors all its own. Estimates of likely Allied casualties from an invasion of the Japanese mainland hovered at around 250,000 American casualties, and many more Japanese ones; but some estimates from respectable sources predicted as many as a million deaths, and some went even higher, numbers that, although staggering, did not seem beyond the range of possibility. (McClay, p. 337)

These diametrically opposed retellings of the end of World War II between McClay and Zinn give way to similarly stark differences in the ensuing years of the Cold War. For one, Zinn attempts to present the Soviet Union as a mere rival to American imperialism, one unnecessarily vilified by American leaders. Zinn suggests, for instance, that President Truman wanted a war economy simply to keep better control of domestic factions, writing:

When, right after [World War II], the American public, war-weary, seemed to favor demobilization and disarmament, the Truman administration … worked to create an atmosphere of crisis and cold war. (Zinn, p. 425)

Zinn’s narrative goes on to further reinforce the idea that while a “rival,” the Soviet Union was artificially portrayed by Truman as anything worse than that:

True, the rivalry with the Soviet Union was real—that country had come out of the war with its economy wrecked and 20 million people dead, but was making an astounding comeback, rebuilding its industry, regaining military strength. The Truman administration, however, presented the Soviet Union as not just a rival but an immediate threat. (Zinn, p. 425)

Zinn goes on to exonerate the Soviet Union for its hand in many communist takeovers of Eastern European countries, positing them simply as popular movements in the wake of the second world war.

In contrast, McClay provides a clear-eyed assessment of Soviet expansionism. Characteristic of his text’s narrative overall, McClay does not give a one-sided account that boils down Soviet motivations exclusively to lust for power and growth. McClay addresses the fact that Russia had been invaded multiple times in living memory by Western forces and rationally desired a buffer. He notes further that Russia had suffered the heaviest losses of the war and was justifiably aggrieved. McClay does not exonerate them, though, declaring instead:

It is an entirely different matter to excuse the unmistakable pattern of Soviet deceptions, manipulations, and broken promises as, one by one … Soviet-controlled Communist regimes came to power in Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia. (McClay, p. 350).

McClay also notes that guiding American policy toward the Soviet Union was the fact that, like many totalitarian states, the USSR was

permeated with internal instability and insecurity, which in turn helped to fuel a ceaseless drive toward expansion. (McClay p. 350).

Students who read McClay, then, come away with an important lesson about authoritarians and dictators as well: Repressive regimes are inherently unstable ones. Howard Zinn’s message to students, though, is that the United States is itself a repressive regime and that it merely used the Cold War as an opportunity to further oppress its own citizens. As he declares:

This combination of [U.S. Cold War] policies would permit more aggressive actions abroad, more repressive actions at home. (Zinn, p. 425).

Through such statements, and his portrayal of the Soviet Union as a mere rival, rather than the perpetrator of untold tens of millions of deaths, Zinn equates two governments whose domestic policies were radically different. Especially considering the successes of the Civil Rights Movement in the latter half of the 20th century, the United States has ensured formal judicial recognition of a far greater number of liberties than would ever exist under the Soviet Union.

While neither McClay nor Zinn’s texts delve deeply into the totalitarian horrors of the Soviet regime within the USSR’s own borders—including the tens of millions of lives brutally extinguished by the Soviet-induced famine in the Ukrainian Holodomor—readers of Zinn are left uniquely uninformed of the nature of this 20th century scourge, primed to view Soviet atrocities as no worse than what they are told was a similarly repressive regime ruling the United States.

Civil Rights

A key component of Marxist rhetoric is the idea that the systems of free market capitalism, liberal democracy, and the Enlightenment ideology have never produced enough positive change to justify their continued existence. The extreme version holds that any system not entirely structured around socialism always has been and always will be oppressive.

This largely explains Zinn’s decision to frame America’s founding as an exercise in establishing a “system of national control.” But no greater example of this worldview exists than in the way Zinn talks about the Civil Rights Movement. So skewed is this narrative that students reading Zinn could easily come to the conclusion the movement was a failure and little changed about America through the efforts of many brave and principled people.

The penultimate paragraph of Zinn’s civil rights chapter begins, for instance, with this:

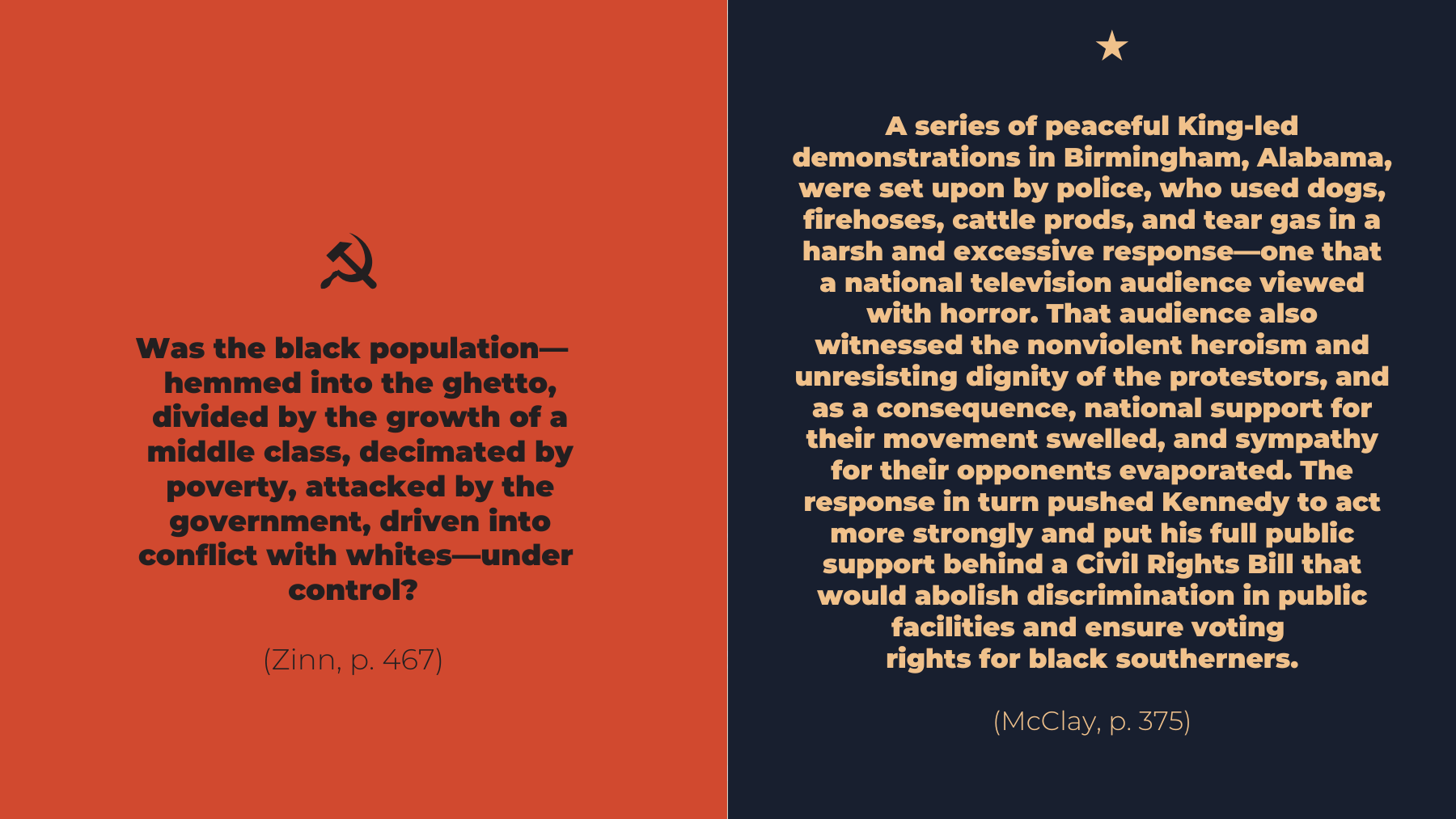

Was the black population—hemmed into the ghetto, divided by the growth of a middle class, decimated by poverty, attacked by the government, driven into conflict with whites—under control? (Zinn, p. 467) .

Few would suggest there were no longer challenges relating to racial equality by the 1970s. Zinn’s framing, however, casts every bit of progress as mere appeasement. For Zinn, the Civil Rights Movement was resolved by a top-down approach in which the ruling class doled out select privileges to quiet down racial agitators.

Contrast that with how McClay describes the effectiveness of Martin Luther King Jr.’s protests in Birmingham:

A series of peaceful King-led demonstrations in Birmingham, Alabama, were set upon by police, who used dogs, firehoses, cattle prods, and tear gas in a harsh and excessive response—one that a national television audience viewed with horror. That audience also witnessed the nonviolent heroism and unresisting dignity of the protestors, and as a consequence, national support for their movement swelled, and sympathy for their opponents evaporated. The response in turn pushed Kennedy to act more strongly and put his full public support behind a Civil Rights Bill that would abolish discrimination in public facilities and ensure voting rights for black southerners. (McClay, p. 375).

Students who read McClay, then, receive the message that civil rights protestors were effective in influencing policy. Young readers are empowered in this way, learning that public opinion, grassroots action, and principled issue advocacy can create powerful reform, rather than conclude that the American experiment is a system of perpetual structural oppression that must be continually resisted and ultimately thrown down.

McClay also avoids the mistake of describing the Civil Rights Movement as a panacea and acknowledges many of the things Zinn chooses to focus on as failings. But unlike Zinn, McClay is still willing to celebrate a victory—even when incomplete—and recognizes the importance of progress, even when it is gradual. As McClay writes:

The Civil Rights Bill would pass in 1964, followed in 1965 by a Voting Rights Act. These did not solve the problem of racial inequality and bigotry in America, but they were a huge step in that direction. (McClay p. 376)

In contrast, Zinn sustains the same condescending hostility toward these advancements as he exhibited toward prior achievements of the republic. Zinn writes:

Attempts began to do with blacks what had been done historically with whites—to lure a small number into the system with economic enticements. (Zinn, p. 464)

Indeed, this language mirrors his account of the America’s founding, which had suggested that policies that allowed for a middle class to thrive “could hold back a number of potential rebellions and create a consensus of popular support for the rule of a new, privileged leadership.” (Zinn, p. 59)

Zinn thus appears to find the existence of a middle class—whether in the age of the founding or the Civil Rights Movement—a societal negative. People living comfortable lives with modest luxuries, stability, and hope for the future—all defining features of the middle class—are obstacles to social revolution, as its members do not share an urgency for the overthrow of the existing political order.

As a result, Zinn’s appraisal of the Civil Rights Movement falls back to the same thesis characterizing A People’s Historythroughout: a belief that anything less than the achievement of total economic equality represents a mere concession to the ongoing systems of oppression. Put simply, while McClay summarizes his own thesis in the title of his work Land of Hope, Zinn’s could perhaps be rebranded as a Land of Despair.

Conclusion

Howard Zinn’s A People’s History advances misrepresentations, lacks nuance, and aims to misinform our young people about landmarks of American history. The book has a near-exclusive focus on understanding every major event as a conflict between capital and labor, borrowing from Marx to scrub individual actors’ motivations free of all principles beyond greed and economic exploitation.

The reason to oppose Howard Zinn’s book in school curricula is not because it criticizes the United States or even solely because of its ideologically driven narrative. The reason to oppose it is because it flattens America’s dynamic history into a simplistic and repetitive thesis of oppression that engenders skepticism and contempt for American institutions within our students. That is why the Van Sittert Center for Constitutional Advocacy advises parents, school leaders, and educators to instead incorporate materials such as Land of Hope as an anchor for their instruction in American history. Our children deserve to know they can have an impact, they can change America for the better, and they will be able to pursue happiness in a free land.

Textbooks presented to high school students need not “whitewash” American history—indeed they should make apparent the periods of our past in which the peoples of this nation have failed to live up to the ideals on which the United States was founded. But trying to convince students that the American republic is thus fundamentally corrupt is an entirely different—and toxic—message.

Works such as Land of Hope avoid these traps, instead highlighting the virtues of America while not shying away from its vices and shortcomings. Such books remind students that ideas and decisions matter and encourage them toward responsible citizenship. In an age of increasing cynicism, stilted portrayals of history, and faltering civic literacy, the richness of texts like Wilfred McClay’s offer a much needed glimmer of hope.

End Notes

[1] “Americans’ Civics Knowledge Drops on First Amendment and Branches of Government,” Annenberg Public Policy Center, University of Pennsylvania, September 13, 2022, https://www.asc.upenn.edu/news-events/news/americans-civics-knowledge-drops-first-amendment-and-branches-government; Megan Brenan, “American Pride Remains Near Record Low,” Gallup, July 2, 2024, https://news.gallup.com/poll/646655/american-pride-remains-near-record-low.aspx.

[2] “Activist and Historian Howard Zinn,” Big Think, December 27, 2010, https://bigthink.com/activist-and-historian-howard-zinn.

[3] A People’s History of the United States: 1492 – Present, Zinn Education Project, https://www.zinnedproject.org/materials/peoples-history-of-the-united-states, accessed September 30, 2024.

[4] Dana Goldstein, “History Teachers Are Replacing Textbooks with the Internet,” New York Times, September 19, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/19/us/social-studies-curriculum.html.

[5] Wilfred M. McClay, Jack Miller Center, https://jackmillercenter.org/team/council/wilfred-mcclay.

[6] Wilfred McClay, Land of Hope, Encounter Books, 2019, 11.

[7] Duberman, Martin, Howard Zinn: A Life on the Left, United States, New Press, 2012.

[8] Paul Glavin and Chuck Morse, “War Is the Health of the State,” Perspectives on Anarchist Theory 7, no. 1, Spring 2003, https://www.howardzinn.org/collection/war-is-the-health-of-the-state/.

[9] McClay, 72.

[10] HB 2008, Fifty-fifth Legislature of Arizona, Second Regular Session, 2022, https://apps.azleg.gov/BillStatus/BillOverview/76249.