Executive Summary

In 2024, more than 7,000 medical school graduates in the United States and abroad failed to secure a residency, keeping highly-skilled medical graduates from entering the healthcare workforce. But by embracing Associate Physicians—a medical school graduate licensed to provide care under the supervision of a physician—states can harness a talented pool of medical graduates to expand healthcare access in our communities.

To date, eleven states have adopted the practice while twelve more are considering bills to allow for Associate Physician status. As of 2024, states have issued 1,220 Associate Physician licenses, with Missouri (876) and Arizona (315) accounting for over 97% of the total. Utah, Missouri, and Louisiana maintain the least restrictive Associate Physician licensing frameworks based on scope of practice, supervision, and other common regulatory factors.

One major hurdle to increasing the number of Associate Physicians in the United States is finding a supervising physician. As few as 25% of those looking to obtain a license secure the required supervision needed to begin practicing medicine.

Based on the following analysis, this report recommends five strategies to reduce barriers to entry for medical graduates seeking Associate Physician licensure.

Introduction

Studies have found that the residency system in the United States has become the primary roadblock for training U.S. physicians, artificially limiting the supply of doctors and undermining efforts to deliver basic, accessible care to patients nationwide.4

Not matching into a residency program—the main pathway to obtaining physician licensure in the United States—remains a daunting reality that thousands of medical students face every year.1,2 This waste of talent stems from a systemic bottleneck in American healthcare that typically leaves over 2,500 American medical graduates and more than 5,000 international medical graduates (U.S. and non-U.S. citizens) without a residency match, effectively keeping them from becoming licensed physicians.3

Note: Estimates of unmatched applicants are based on the 2024 MATCH from the National Resident Matching Program and do not include the number who found positions through the Supplemental Offer and Acceptance Program (SOAP). 3

Rather than waiting another year to reapply for a residency position and begin providing care as doctors, medical graduates could enter the workforce by becoming Associate Physicians. Under the supervision of a licensed physician, they could put their clinical skills and medical education to work immediately, allowing an alternative path to hone their abilities while contributing to patient care.3

Free-market policymakers have already identified mechanisms to integrate the pool of unmatched medical graduates into the healthcare system while allowing them the opportunity to gain experience and earn a living. In 2014, Missouri became the first state to enact Associate Physician legislation. Over the past decade, the practice has spread across eleven states (Image 1), with eight states currently issuing licenses. In 2024, twelve states began debating similar reforms.4

This report employs the term “Associate Physician” for consistency, but states use a variety of names for the role, including “Assistant Physician,” “Bridge Year Physician,” and “Graduate Physician.”6

Image 1: Map of Associate Physician Legislation (Link to interactive map).

*Timeline and name of each state’s Associate Physician Legislation is here. See Appendix A. for state specific AP laws. Data was retrieved from the Federation of State Medical Boards, February 2025.6

Objective

The regulatory landscape for Associate Physician licenses varies considerably by state in scope of practice, supervision requirements, eligibility criteria, geographic restrictions, prescriptive authority, and other factors. While certain safeguards across all states remain consistent, some differing regulatory aspects may deter the practice more than others, reducing the likelihood that medical graduates or supervising physician participate in the programs. This study aims to (1) quantify this legislation by state and identify barriers that may hinder the utilization of this license, and (2) explore the usage and safety of Associate Physicians in the United States.

Methodology

To conduct this analysis, researchers created an index to compare different Associate Physician policies between states and to assess the degree of freedom/restrictiveness of each state’s laws. The index incorporated 15 key metrics based on reoccurring themes in each state’s legislation (Table A.). The metrics included both continuous and non-continuous variables. Non-continuous variables were converted into ordinal scores where higher scores indicated more freedom and fewer restrictions on an Associate Physician’s ability to practice.

For example, “Are Associate Physicians required to practice in a rural or Medically Underserved Area?” Yes = 0, No = 1. A “No” response (the higher score), signified no limitations on where this individual may practice.

Table A. Index Metrics

(Common regulatory factors that emerged in legislation and rules):

|

Each metric was normalized using standard deviation and statistical Z-scores. This approach measured how each state’s Associate Physician policies differed from the average of all other states. While many indices used robust Z-scores (using the median instead of the mean), this limited the effect of outliers. Considering many states pass laws modeled on other states, highlighting those outliers was preferable.

A few metrics were adjusted by subtracting two standard deviations from its score if it was inherently linked and dependent on another metric. For example, when considering if states cap the number of years a licensee may be licensed as an Associate Physician, a state was first scored on whether it capped the number of years someone may be an Associate Physician and then, if so, how many. When creating a mini-composite index of those two metrics, any state that did not cap the number of years would be considered freer than any state that does. Then states that do cap the number of years would be scored and ranked accordingly on the number of years an Associate Physician may renew their license and practice.

Each metric contributed an equal weight to the index, making up 1/14 or 7.14% of a state’s total score. This methodology has been used in similar composite indices such as The Cato Institute’s “Freedom in the 50 States” or the “City Freedom Index” at the Beacon Center of Tennessee and meets the standards outlined in the Handbook on Construction Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide.7,8,9

Apart from the index, the total number of Associate Physician licenses issued was calculated by summing the number of licenses that have been granted since each state’s program began, including active and expired licenses, as well as individuals who renewed their license multiple times. The researchers experienced different response times from the boards and collected the data between July 2024 and September 2024. Missouri was the only state where data was collected in September 2024.

Besides total license usage, the number of active licenses was calculated by summing the number of licensees who had a valid license at the time of data collection. The percentage that was supervised and practicing was calculated by taking the total number of licenses that have been granted divided by the number of Associate Physicians who found a supervising physician and practice. Finally, adverse action reports and disciplinary information were requested from each state board to assess the safety of this profession.

Results

Quantifying License Freedom

This analysis revealed that Utah (Rank: 1), Missouri (Rank: 2), and Louisiana (Rank: 3) have the most permissive Associate Physician licenses, while Alabama (Rank: 7) and Arizona (Rank: 8) impose the most restrictions regarding scope of practice, supervision, and other common regulatory factors (Image 2). Despite ranking among the freest, both Louisiana and Missouri limit this role to primary care settings. Missouri also mandates that Associate Physicians work in Medically Underserved Areas (MUA), further limiting where these individuals can provide care. Among states with available licenses, only a few have either the MUA (Kansas and Missouri) or primary care requirements (Louisiana and Missouri).

Image 2: Map of Freedom Ranking (Link to interactive map)

*Note: The index scores for each state’s common regulatory categories, fees, and more, available here. **During the time of the analysis, only eight states had a license available to apply for, excluding Tennessee, Florida, and Maryland from the index evaluation.

Eligibility

States demonstrated significant variation in who can apply for an Associate Physician license based on geographic residency status or location of their medical school. The most restrictive states in this category were Arkansas, which only allows either in-state residents or applicants from an in-state medical school, and Kansas, which only allows graduates from The University of Kansas Medical School—potentially explaining why the state has produced zero license holders since its program began.

Most states permit out-of-state applicants, including international medical graduates (IMGs), provided they have completed their education at an accredited medical school. Only six states (Louisiana, Missouri, Utah, Arizona, Maryland, and Tennessee) allow IMGs from medical schools outside the United States and Canada. Among them, three (Missouri, Utah, and Maryland) require international medical graduates to have Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG) certification. The ECFMG verifies the authenticity of an international medical graduate’s credentials and serves as a safeguard for states, ensuring that applicants meet American standards and qualifications.

Similar to applying for a residency, many states require unmatched medical graduates to have recently completed medical school within the past two or three years, but Idaho and Louisiana require applicants to have graduated medical school within the past year.

Apart from being recent medical graduates, half of the states require medical graduates to have applied and been unsuccessful in the MATCH. Some states, such as Arizona, go further by mandating three residency applications per year following their initial license. This poses a burden on Associate Physicians, as it involves gathering certifications, transcripts, personal statements, and letters of recommendation.

Most states treat the Associate Physician role as a stepping stone to residency, limiting how long one can practice to two to three years. However, Missouri is the only state that allows Associate Physicians to work indefinitely without a time restriction. Apart from Missouri, Utah has one of the most lenient caps (six years), while Idaho enforces the strictest cap, barring individuals from practicing after one year.

Supervision

The number of Associate Physicians a license physician may supervise varies across states. Kansas and Louisiana place no specific limits on the number of Associate Physicians a physician can supervise, while Missouri and Idaho impose relatively high caps (six supervisees). By contrast, Arizona imposes the most restrictive policy, allowing only one licensee per physician. The type of supervision (e.g. direct vs. indirect) also varies by state with licenses requiring a physician’s oversight to be provided in person or on-site while others allow remote supervision.

Arkansas is the only state that requires direct supervision for the entirety of the license, whereas some states implement both types of supervision throughout the process. Half of states (Missouri, Louisiana, Kansas, and Utah) allow for more independent supervision after a probationary period. For example, Missouri allows Associate Physicians to practice within a 75-mile radius after one month of direct supervision.

Supervising physicians also face regulatory burdens. For example, in Louisiana, a physician looking to supervise must complete mandatory training, while in Kansas the physician needs to have known the Associate Physician applicant for at least one year prior to supervising them. Meanwhile, in Arkansas, a physician must appear in person before the board with the applicant before a license will be granted.

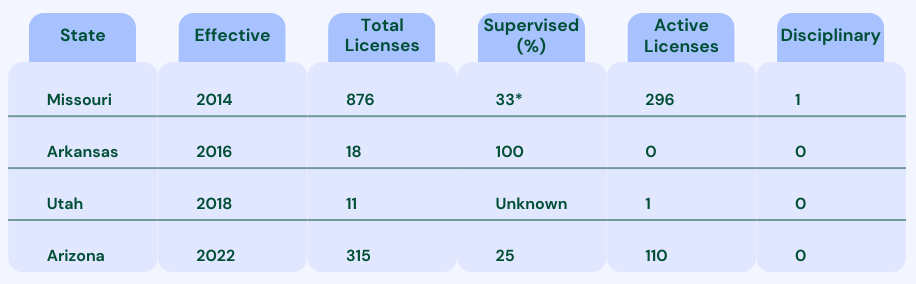

License Usage and Safety

States have issued a total of 1,220 Associate Physician licenses, with Missouri (876) and Arizona (315) accounting for over 97% of the total (Table 1). Half of the states with available licenses (Idaho, Louisiana, Kansas, and Alabama) have had zero applicants. Arkansas is the only state requiring graduates to obtain a supervising physician before submitting an application, resulting in a lower number of licenses that have been granted (18) but a higher percentage of applicants who secured supervision.

Table B. Usage of Associate Physician Licenses by State

*Louisiana, Idaho, Alabama, and Kansas were not included because they had zero license holders at the time of data collection. Missouri’s calculation for the percentage supervised is explained in the Limitations section.

Arizona has had a total of 315 licenses since the program began in 2022. However, some individuals have applied multiple times, leaving 286 unique applicants. Among all licenses granted by the state, approximately 25% of applicants found a supervising physician while 33% in Missouri found supervising physicians. Utah was the only state that did not collect data on supervision.

At time of data collection, Missouri had 296 active licenses, followed by Arizona (110) and Utah (1). Across all the issued licenses, only one has been revoked. Apart from this, researchers found no evidence of additional disciplinary actions or adverse reports concerning an Associate Physician.

Alternative Pathway to Physician Licensure

Since 2024, several states (Florida, Oklahoma, Hawaii, Maryland, New Hampshire, Connecticut, New Jersey, and Nevada) have introduced Associate Physician legislation. Additionally, two states with existing licenses available (Arizona and Idaho) have introduced bills to expand pathways to physician licensure for candidates who meet specific requirements (Image 3).10, 11,12,13

Image 3: Bills in 2024/2025 Session (Link to interactive map).

*Data retrieved in February 2025

Despite growing interest in Associate Physicians, no state has established the practice as an alternative pathway to physician licensure. Critics argue that it remains unproven whether the experience as an Associate Physician is comparable to a residency, which includes a structured curriculum of clinical rotations in a variety of areas of medicine, weekly lectures, simulations, and other training exercises. 14

Supporters of the Associate Physician pathway contend that if completing one or two years of residency after medical school—along with passing Step 3 of the USMLE—qualifies physicians in most states to practice as general practitioners, then three or more years of experience as an Associate Physician, combined with passing the same exam, should also serve as a path to general practitioner licensure.15

Discussion

In 2024, residency applications reached an all-time high of approximately 50,000, underscoring that the ongoing physician shortage stems not from a lack of aspiring doctors, but from artificial barriers to entry. Market-driven reforms provide a potential solution to addressing a dysfunctional system that fails to meet public health demands.12

This research demonstrates that granting Associate Physician licenses to medical school graduates who do not match into a residency could be a viable strategy. The data indicate that the Associate Physician role is safe and could serve as a long-term career option an alternative path to general practitioner licensure.

More than 1,200 Associate Physician licenses have been granted in the United States, with Missouri and Arizona leading the implementation. Arizona, despite ranking last on the freedom index, has reported higher license utilization than many other states. This discrepancy likely stems from eligibility requirements, the diversity and the size of the state, and other factors that make the state more attractive to international medical graduates.

Beyond regulatory challenges, a shortage of supervising physicians has hindered the expansion of Associate Physicians in several states. Although these factors extend beyond the scope of this report, policymakers should consider why so few physicians are willing to supervise Associate Physicians, including concerns about liability, time commitment, and other regulatory factors. For example, states such as Arizona and Missouri, which are attractive to populations for international medical graduates, could engage an additional 100-300 healthcare providers on a yearly basis if supervisory obstacles were resolved (Table 1).

Free-market solutions exist to address shortages in medical care. Studies indicate that finding ways for all Associate Physicians to obtain a supervising physician and practice medicine would substantially strengthen a state’s healthcare workforce. For example, The CATO Institute in 2023 found that adding 292 licensed Associate Physicians to the state of Missouri could increase the entire primary care workforce by 3%.13 Allowing non-residency medical school graduates to practice their craft will help fill the growing gap in medical access for those who need it most.16

The entrenched bottleneck within the current medical residency system in the United States lacks a simple solution.17 However, Associate Physician licensing offers a pragmatic reform that could mitigate some of the most harmful effects. As of February 2024, eleven states had enacted Associate Physician legislation, while twelve others had begun considering the reform.18

Key Recommendations

It is critical that the Associate Physician role be tailored to those who would utilize it most—unmatched medical graduates or those who depart from residency early and need another pathway to practice. Below are five recommendations for states that are considering policy reforms to lower barriers for medical graduates interested in becoming Associate Physicians and for the physicians that supervise them.

- Include a Wide Population of Applicants

License usage tends to be higher among states that permit a larger population of applicants (e.g., international medical graduates (IMGs) and out-of-state residents) compared to states that impose stricter eligibility requirements, such as allowing only in-state residents or individuals from a certain medical school to apply. IMGs (U.S. citizens and non-citizens) comprised 32% of all residency applicants nationwide, highlighting the importance of expanding eligibility for this license. In the 2024 MATCH, only 63% of the 14,000 IMGs received a residency placement compared to graduates of U.S.-based medical schools (93%).19, 20

As of 2024, only four states—Louisiana, Missouri, Utah and Arizona—allow IMGs from medical schools outside the United States and Canada to apply to be Associate Physicians, with Missouri and Utah being the only states that require IMGs to have Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG) certification.

- Place No Constraints on Where They Can Practice

Although well-intended, geographic mandates—such as limiting Associate Physician licensure to rural settings—ultimately decreases the number of potential Associate Physicians who could enter the workforce. A study by the Journal of International Medical Graduates found that many medical graduates face logistical barriers connected to a lack of transportation, communication infrastructure, and other factors, limiting their ability to see patients or engage with other healthcare providers.21

Another pressing matter is that the designations of areas as medically underserved are often outdated. Forcing skilled medical providers into areas that may not be underserved risks diverting talent from places that truly needs them. A 2024 study by the Paragon Health Institute revealed that if the federal government updated its methodology, thousands of communities would lose their shortage area classification.22

- Treat it as a Life Profession

No matter why graduates are unable to complete a residency, alternative pathways should exist for individuals who complete medical school and want to apply their training in the workforce. Whether they use the license as a pathway to residency or pursue it as a career, this role should have no cap on the number of years an individual can work and practice.

- Do not Mandate Applications to a Residency Program

Half of the states with Associate Physician licenses require medical graduates to reapply and be unsuccessful in the MATCH. There are several reasons individuals may not want to do a residency program or depart from a residency early (e.g., mistreatment from faculty, change of specialty.). Some primary care specialties, such as family medicine, pediatrics, and obstetrics and gynecology, have reported increased retention difficulties, with women and IMGs more likely to withdraw.23, 24 Associate physicians can address this shortfall.

- Decrease Burdensome Requirements for the Supervising Physician

Regulators should encourage licensed physicians to serve in supervisory roles for Associate Physicians. Instead, several states impose onerous supervision requirements, including pre-existing relationships of at least one-year, mandatory training, and several other restrictions imposed by medical boards that make supervision extremely burdensome.

For example, instead of requiring an individual Collaborative Practice Agreement in which the terms are decided by the supervising physician and the collaborating Associate Physician, several state laws mandate board approval for scope of practice, supervision, and other duties. This added layer of bureaucracy only discourages physicians from acting as supervisors.

Maryland, which was not included in this report, is the only state to delegate the scope of practice, supervision, and other aspects of the Associate Physician license to the employer, provided they align with national medical standards.25

Limitations

This research sought to explore and better understand the Associate Physician programs enacted by eleven states. By nature, this analysis has certain limitations and relies on the clarity of each state’s rules and laws and the discretion of each state’s regulatory board. Apart from data collected for the index, some state boards have maintained poor-quality records or have not collected certain variables, resulting in discrepancies in reporting related to the number of Associate Physicians who are supervised and actively practicing.

Apart from Utah, which did not collect supervision data, Missouri was the only state whose quantitative data presented significant challenges. In fact, its dataset did not align with the information published on its website. The board stated that they had technological limitations, and the researchers had to utilize two different sources to calculate the percentage who was supervised. To calculate this percentage, the researchers utilized the denominator that was emailed directly from the board (876) and the numerator that was calculated from the raw dataset leading to the percentage supervised of 33%. Supervision rates for all states were calculated based on data that spanned the entire time that licensure became available, which led to a various across different years.

The researchers sought to enhance the reliability and validity of the index by including a broad range of metrics to assess the freedom of the licenses. However, not all indicators could be included. Also, in situations where legislation and rules were unclear or omitted certain metrics, the researchers followed up with state boards to fill in the missing information. If the legislation differed from the information provided by the boards, the researchers deferred to the board’s position, capturing their response within the index. Overall, the ambiguities within the laws increased the potential for error. For states such as Missouri and Utah, which amended their laws, the policy changes have been reflected in the index.

Appendix A: Enacted State Legislation for Associate Physician, February 2025

| States | Title | Legislation |

| AL | Bridge Year Graduate Physician | SB 155 (2023) |

| AZ | Medical Graduate Transitional Training Permit | SB 1271 (2021) |

| AR | Graduate Registered Physician | HB 1162 (2015) |

| FL | Graduate Assistant Physician | SB 716 (2024) |

| ID | Bridge Year Physician | H 153 (2023) |

| KS | Special Permit | HB 2225 (2015) |

| LA | Bridge Year Graduate Physician | SB 439 (2022) |

| MO | Assistant Physician | SB 716 (2014), SB 718 (2018) |

| MD | Supervised Medical Graduate | HB 757 (2024) |

| TN | Graduate Physician | SB 937 & HB 1311 (2023) |

| UT | Associate Physician | HB 396 (2017), HB 400 (2022) |

End Notes

[1] The Road to Becoming a Doctor. Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), 2020. https://www.aamc.org/media/36776/download.

[2] Hanson, Melanie. “Average Medical School Debt” EducationData.org, August 2024,

https://educationdata.org/average-medical-school-debt.

[3] Based on data from The National Resident Matching Program (NRMP), Results and Data 2024 Main Residency Match, data through June 2024, https://www.nrmp.org/match-data/2024/06/results-and-data-2024-main-residency-match/.

[4] Orr, Robert, “Unmatched: Repairing the U.S. Medical Residency Pipeline” Niskanen Center, September 2021, https://www.niskanencenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Unmatched-Repairing-the-US-Residency-Pipeline.pdf.

[5] Qualifications of an Assistant Physician. Association of Medical Doctor Assistant Physicians, https://assistantphysicianassociation.com/projects.

[6] Based on data from the Federation of State Medical Boards, States with Enacted and Proposed Associate Physician Legislation State by State Overview, updated February 2025, https://www.fsmb.org/siteassets/advocacy/policies/associate-physician-legislation-by-state-key-issue-chart.pdf.

[7] Freedom in the 50 States. CATO Institute, January 2023. https://Freedominthe50states.org.

[8] 2020 Freest Cities in Tennessee. Beacon Center of Tennessee, 2020. https://www.beacontn.org/freest-cities.

[9] Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), August 2008. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264043466-en.

[10] Based on data from the Federation of State Medical Boards, States with Enacted and Proposed Associate Physician Legislation State by State Overview, updated February 2025, https://www.fsmb.org/siteassets/advocacy/policies/associate-physician-legislation-by-state-key-issue-chart.pdf.

[11] Arizona Senate Bill 1507, https://www.azleg.gov/legtext/52leg/2r/bills/sb1507s.pdf.

[12] Idaho House Bill 418, https://legislature.idaho.gov/wpcontent/uploads/sessioninfo/2024/legislation/H0418.pdf.

[13] Idaho House Bill 77, https://legislature.idaho.gov/sessioninfo/2025/legislation/H0077/.

[14] Freeman, Bradley D. “The Implications of Missouri’s First-in-the-Nation Assistant Physician Legislation.” Journal of graduate medical education, 2016, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4763385/.

[15] Singer, Jeffrey, and Pratt, Spencer. “Expand Access to Primary Care: Remove Barriers to Assistant Physicians.” CATO INSTITUTE, April 2023, https://www.cato.org/briefing-paper/expand-access-primary-care-remove-barriers-assistant-physicians.

[16] Singer, Jeffrey, and Pratt, Spencer. “Expand Access to Primary Care: Remove Barriers to Assistant Physicians.” CATO INSTITUTE, April 2023, https://www.cato.org/briefing-paper/expand-access-primary-care-remove-barriers-assistant-physicians.

[17] Based on data from The National Resident Matching Program (NRMP), Results and Data 2024 Main Residency Match, data through June 2024, https://www.nrmp.org/match-data/2024/06/results-and-data-2024-main-residency-match/.

[18] Based on data from the Federation of State Medical Boards, States with Enacted and Proposed Associate Physician Legislation State by State Overview, updated February 2025, https://www.fsmb.org/siteassets/advocacy/policies/associate-physician-legislation-by-state-key-issue-chart.pdf.

[19] Based on data from The MATCH National Resident Matching Program (NRMP), Charting Outcomes: Characteristics of International Medical Graduates who Matched to their Preferred Specialty, August 2024, https://www.nrmp.org/match-data/2024/08/charting-outcomes-characteristics-of-international-medical-graduates-who-matched-to-their-preferred-specialty-2024-main-residency-match/.

[20] Based on data from The National Resident Matching Program (NRMP), Results and Data 2024 Main Residency Match, data through June 2024, https://www.nrmp.org/match-data/2024/06/results-and-data-2024-main-residency-match/.

[21] Kumar, Harendra, and Sharma, Vagisha. “The Impact of International Medical Graduates on Rural Healthcare in the USA: Challenges and Opportunities.” Journal for International Medical Graduates, August 2023, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/373456015_The_Impact_of_International_Medical_Graduates_on_Rural_Healthcare_in_the_USA_Challenges_and_Opportunities.

[22] Finerfrock, Bill, “Where are Provider Shortages: Reassessing Outdated Methodologies” Paragon Health Institute, April 2024, https://paragoninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/State-Health-Care-Policy.pdf.

[23] Wang, Xixi, et al. “Residency Attrition and Associated characteristics, a 10-Year Cross Specialty Comparative Study.” Journal of Brain and Neurological Disorders, vol. 5,4, 2022, https://www.auctoresonline.org/article/residency-attrition-and-associated-characteristics-a-10-year-cross-specialty-comparative-study.

[24] Griffith, Max et al. “Exploring Action Items to Address Resident Mistreatment through an Educational Workshop.” The western journal of emergency medicine, December 2019, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6948710/.

[25] Maryland House Bill 757, https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/mgawebsite/Legislation/Details/hb0757?ys=2024RS.