About the 340B Program

Originally established by Congress in 1992, the 340B Drug Discount Program was created to help healthcare providers that serve low-income and uninsured patients to purchase drugs at a discounted price.[1] The program, commonly referred to as 340B, refers to the authorizing statute, Section 340B of the Public Health Service Act (42 U.S.C. § 256b), which requires manufacturers that participate in the Medicaid Program to offer certain outpatient drugs to “covered entities” at discounted prices. Covered entities include hospitals and Federally Qualified Health Centers, as well as a wide array of other providers, including those caring for rural and medically underserved populations.[2]

As concern over the cost of prescription drugs remains at the forefront of political debate and public concern, Americans as well as their Congressional and state representatives should understand and publicly debate how well the 340B is serving the state’s most vulnerable patients.

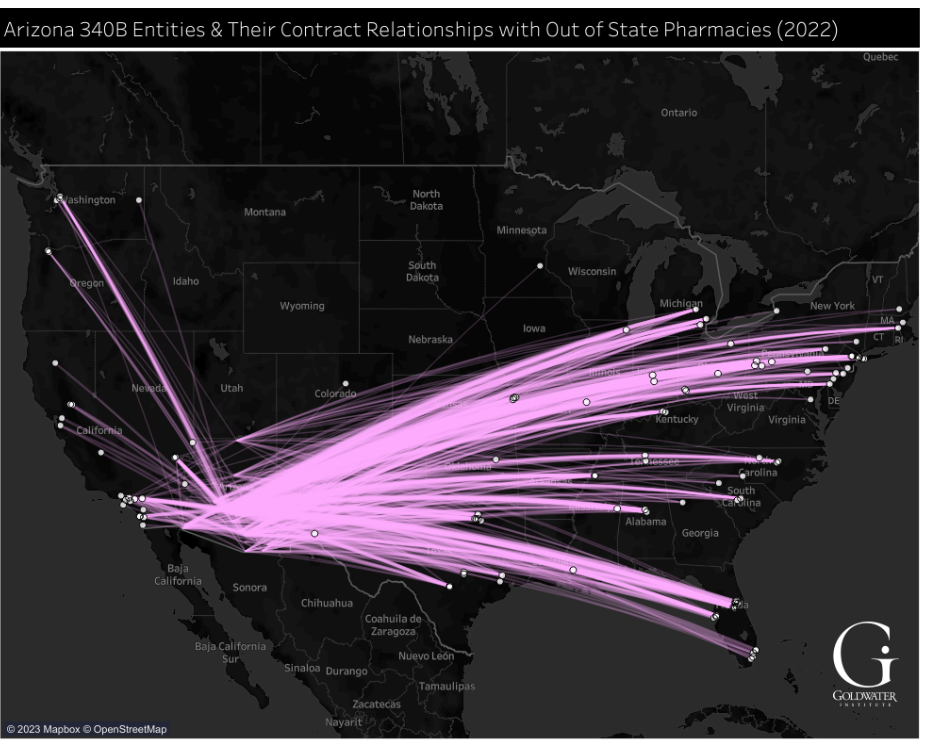

In Arizona, for example, the prescription drugs provided through the program are being made available to contract pharmacies across the U.S. with little or no accountability to the public, lawmakers, or the patients the program is intended to serve.[3] See Figure 1. The program is not only morphing well beyond its original purpose, it may be doing so at the expense of taxpayers and the country’s most vulnerable patients.

Figure 1:

Arizona’s 340B Entities and Their Relationships with Out-of-State Pharmacies, October 2022

To view the interactive version of this figure, click above or click here.

At a minimum, information should be transparent and easily accessible regarding how this program is being used, who is benefitting, and whether it is shoring up the healthcare safety net or simply lining pockets. More specifically, two key questions need answers: Should these entities be allowed to sell discounted drugs at a profit, either to commercially insured patients or other pharmacies? And if so, should restrictions or requirements be placed on the use of these profits?

340B’s Disturbing Lack of Transparency

Imagine a government program that allowed healthcare providers caring for the indigent to purchase drugs at discounts similar to those allotted to other government programs, including the Veterans Health Administration (VA) and Medicaid. Now imagine that state Medicaid programs and the VA were selling these discounted drugs, which were supposed to provide treatments to their programs’ patients, to other state and out-of-state pharmacies, and various affluent areas. And that they were doing this with little or no accounting of where the revenues from the sales were going, who was benefitting, and, in some cases, if indigent patients were getting these treatments but not any associated discounts. Sadly, this is what is now transpiring under the 340B program.

Take the cancer drug treatment Keytruda, for example. A recent New York Times investigative report revealed that a 340B hospital in Richmond, Virginia, purchases a vial of the treatment for $3,444 but then charges a commercial insurer $25,425 for that same vial.[4] Program advocates maintain these resales are justified because the “markups” can be used to fund indigent care and other healthcare services for needy patients.[5] However, there is no accountability as to who gets the discounted treatments, where the extra revenue is going, and to what extent the discounts are being passed to the vulnerable populations that actually need them.

The federal government’s own investigations and audits of the program, as well as more recent media coverage program, highlight the following:

- the lack of program oversight and requirements to document the scope of care being provided to low-income patients under the program,[6]

- concern over covered entities receiving duplicate discounts from both the Medicaid Program and 340B, and[7]

- the disturbing trend of 340B-covered entities “selling” the 340B drugs to commercially insured patients,[8] or selling them at a profit to contract pharmacies in affluent areas or to out-of-state contract pharmacies.[9]

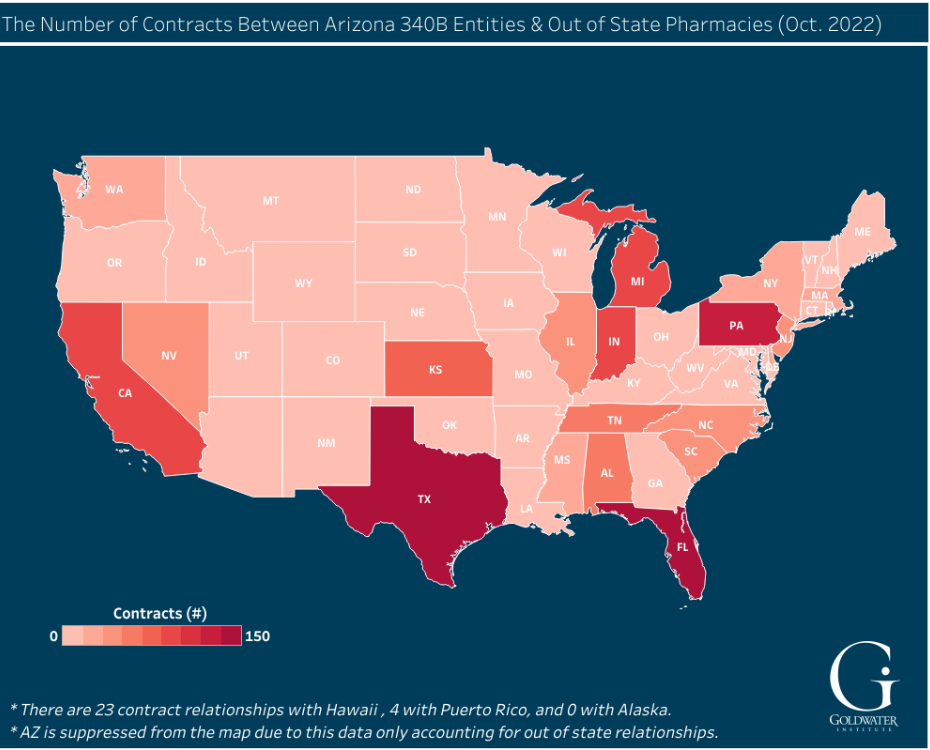

In Arizona, for example, 340B-covered entities in the state have contract pharmacies in 33 other states.[10] See Figure 2. These entities alone have more than 100 contract pharmacies each in three states (Texas, Florida, Pennsylvania), accounting for a total of 420 contract pharmacies. When adding in the next three states with 90 or more contract pharmacies (California, Michigan, Indiana), that total is just under 700 pharmacies outside of Arizona that can obtain the drug treatments made available to Arizona 340B entities. One is left wondering how well this program is serving Arizona’s most vulnerable patients.

Figure 2:

The Number of Contracts between Arizona 340B-Covered Entities & Out-of-State Pharmacies, October 2022

To view the interactive version of this figure, click above or click here.

The difference between drug list prices and what the covered entities pay for the discounted drugs is about $50 billion nationally.[11] A recent Research Letter in the JAMA Health Forum suggests that a growing share of the program beneficiaries are found among more affluent communities and the facilities serving those patients. The analysis examined contract pharmacy growth between 2011 and 2019 and found that “contract pharmacy growth was concentrated in affluent and predominantly White neighborhoods, whereas the share of 340B pharmacies in socioeconomically disadvantaged and primarily non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic/Latino neighborhoods declined.”[12]

The absence of protections ensuring that the most vulnerable patients are benefitting from this government program, as well as the lack of program accountability and integrity, should make careful evaluation and transparency of the 340B program an important healthcare priority for lawmakers. After all, evaluating a program based on its intent rather than its real-world outcomes is a disservice to the taxpayers footing the bill for indigent care and to those patients whose access to needed treatments remains limited but would otherwise be available under the program.

Laws and Rules That Changed the Program

Beginning in 1996, the 340B program allowed covered entities that didn’t have an in-house pharmacy to use one outside pharmacy for self-administered drugs.[13] For example, a community health center that didn’t run its own in-house pharmacy might need to contract with an outside pharmacy so eligible patients could obtain the prescription drugs provided through the 340B program.

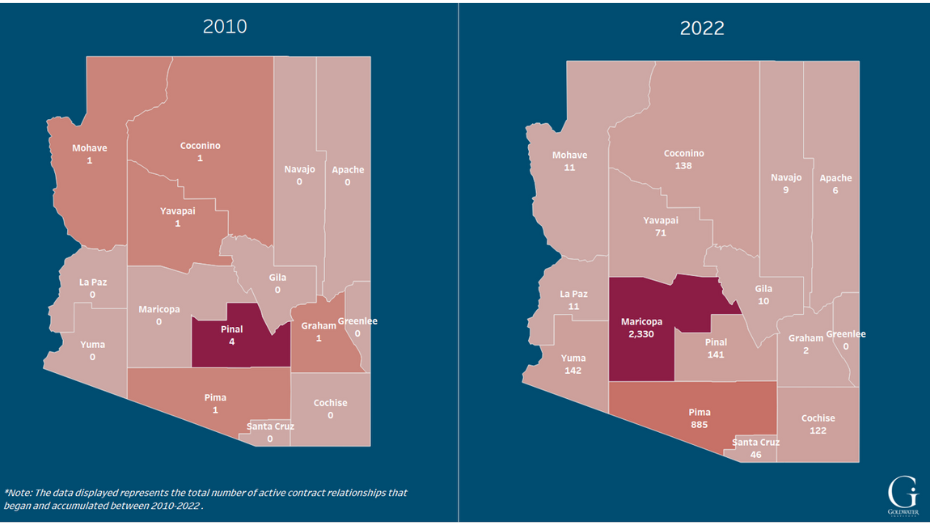

As part of the Affordable Care Act in 2010 and federal guidance, the list of eligible covered entities was expanded and all 340B entities were allowed to contract with an unlimited number of contract pharmacies.[14] As a result, the number of covered entities and the number of contract pharmacies skyrocketed, with little added program accountability and oversight.

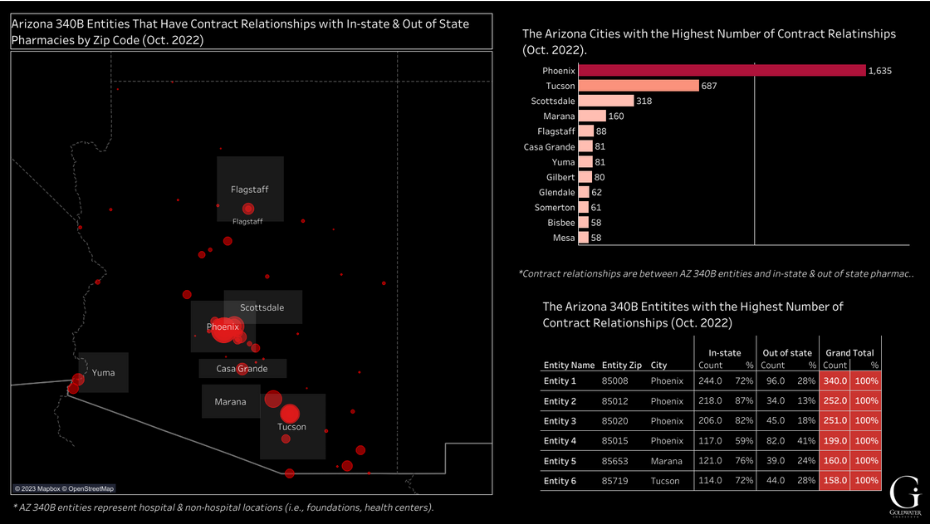

In 2010, five new contract relationships were established by 340B entities in Arizona’s Yuma, Maricopa, Pinal, and Pima counties. By 2022, a total of 3,498 contract relationships had been established. See Figure 3. One 340B entity in Phoenix has more than 300 contract relationships—almost 100 of them with pharmacies in other states across the country. See Figure 4. (For purposes of this analysis, covered entity names have been suppressed.)

Figure 3:

Contract Relationships by Year between 340B Entities in Arizona and

In- & Out-of-State Contract Pharmacies, 2010 vs. 2022

To view the interactive version of this figure, click above or click here.

Ongoing Challenges

The unchecked, explosive growth of contract pharmacies raises the important question of if and to what extent the 340B program is meeting the program goal of helping providers serve their low-income and uninsured patients. This unchecked growth is causing growing uncertainty and confusion about the program’s future.

Failed legislative attempts to impose more program accountability and oversight has led to multiple, unilateral attempts by manufacturers to establish their own sets of discount policies and price restrictions on entities using contract pharmacies to purchase 340B drugs. The response by some members of Congress has led to the Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) issuing violation letters to the manufacturers, who then issued legal challenges to the violation letters, which led to conflicting legal rulings on whether manufacturers are required to provide 340B discounts to contract pharmacies.[15] It is unlikely that this added uncertainty and confusion will subside quickly absent substantial legislative or legal action. The current state of the 340B should serve as a call to action for key stakeholders, patient advocates, and lawmakers.

Figure 4:

Arizona 340B Entities with the Highest Number of Combined

In- & Out-of-State Contract Pharmacies, October 2022

To view the interactive version of this figure, click above or click here.

What Lawmakers Can—and

Should—Do

Decades of counter-productive policies coupled with a lack of clear program intent and goals should not be allowed to continue indefinitely. There are important first steps lawmakers can take.

State lawmakers can establish billing policies for 340B claims. In the case of Arizona, for example, lawmakers should

Revisit Arizona’s 340B statute.[16] The federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services does not require state Medicaid agencies to set 340B policies, but states may establish billing policies for 340B claims. Arizona’s statute was created before the massive expansion of the program’s covered entities and current unchecked growth of contract pharmacies. State lawmakers have the authority and responsibility to update billing policies and restore, to the extent possible, program transparency and financial integrity.

Congressional lawmakers should

End statutory ambiguity on the number and use of contract pharmacies. Congress has the authority to amend the 340B statute to clarify and impose restrictions on the use, number of, and allowable financial transactions related to covered entities’ use of contract pharmacies. Congress should also require greater transparency on the financial transactions related to the program.

General principle:

Under no circumstance should an uninsured or indigent patient be charged more than the price that the covered entity paid for a drug obtained through the 340B program. These incidents, as documented by the GAO, are unconscionable and run counter to any spirit of patient assistance.

Americans deserve to know if and how a government program is benefitting entrenched interests at the expense of the state’s most vulnerable patients. At a minimum, information should be transparent and easily accessible regarding how this program is being used, who is benefitting, and whether it is helping to shore up the healthcare safety net or lining the pockets of other institutions.

According to the federal government’s own reports and audits, many of the discounts that should be benefitting the nation’s uninsured and indigent patients are not being passed along to these patients. Meanwhile, entities covered in Arizona in and many other states are sending drug treatments to pharmacies across the country.

Lawmakers who are serious about “doing something” about prescription drug access and prices should make 340B reform a top priority. Program transparency and integrity are the best places to start.

To download the print version of this report click here.

End Notes

[1] Veteran’s Health Care Act of 1992, P.L. 102-585, https://www.hrsa.gov/opa/program-requirements/public-law-102-585.

[2] For a full list of currently eligible entities, see the Health Resources & Services Administration at https://www.hrsa.gov/opa/eligibility-and-registration.

[3] Based on data from Health Resources & Services Administration, 340B Office of Pharmacy Affairs Information System, data through October 2022, https://340bopais.hrsa.gov/.

[4] Katie Thomas and Jessica Silver-Greenberg, “How a Hospital Chain Used a Poor Neighborhood to Turn Huge Profits,” New York Times, updated September 27, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/24/health/bon-secours-mercy-health-profit-poor-neighborhood.html?smid=tw-share.

[5] Henry A. Waxman, “30 Years of 340B: Preserving the Health Care Safety Net,” Health Affairs, December 7, 2022, https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/30-years-340b-preserving-health-care-safety-net. Now Chairman of Waxman Strategies (waxmanstrategies.com), he also served as chairman and ranking member of the Energy & Commerce Committee’s Subcommittee on Health and the Environment, which has jurisdiction over the 340B program.

[6] U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), “340B Drug Discount Program: Increased Oversight Needed to Ensure Nongovernmental Hospitals Meet Eligibility Requirements,” GAO Report to Congressional Requesters, December 2019, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-20-108.pdf.

[7] U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), “Drug Pricing Program: HHS Uses Multiple Mechanisms to Help Ensure Compliance with 340B Requirements,” GAO Report to Congressional Requesters, December 2020, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-21-107.pdf.

[8] Thomas and Silver-Greenberg, “How a Hospital Chain Used a Poor Neighborhood.”

[9] Anna Wilde Mathews, Paul Overberg, Joseph Walker, and Tom McGinty, “Many Hospitals Get Big Drug Discounts. That Doesn’t Mean Markdowns for Patients,” Wall Street Journal, December 20, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/340b-drug-discounts-hospitals-low-income-federal-program-11671553899?mod=article_inline.

[10] Based on data from Health Resources & Services Administration, 340B Office of Pharmacy Affairs Information System, January – October 2022, https://340bopais.hrsa.gov/.

[11] Adam J. Fein, Ph.D., “The 340B Program Climbed to $44 Billion in 2021 – With Hospitals Grabbing Most of the Money,” Drug Channels, August 15, 2022, https://www.drugchannels.net/2022/08/the-340b-program-climbed-to-44-billion.html.

[12] John K. Lin, M.D., MSHP; Pengxiang Li, Ph.D.; Jalpa A. Doshi, Ph.D.; and Sunita M. Desai, Ph.D., “Assessment of U.S. Pharmacies Contracted With Health Care Institutions Under the 340B Drug Pricing Program by Neighborhood Socioeconomic Characteristics,” JAMA Health Forum, June 17, 2022, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama-health-forum/fullarticle/2793530.

[13] Karen Mulligan, Ph.D., “The 340B Drug Pricing Program: Background, Ongoing Challenges and Recent Developments,” USC Schaeffer White Paper, October 14, 2021, https://healthpolicy.usc.edu/research/the-340b-drug-pricing-program-background-ongoing-challenges-and-recent-developments/.

[14] 75 Fed. Reg. 10272 (March 5, 2010), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2010-03-05/pdf/2010-4755.pdf.

[15] Hannah-Alise Rogers, “Overview of the 340B Drug Discount Program,” Congressional Research Service In Focus, October 14, 2022, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF12232.