Executive Summary

Telehealth holds tremendous potential for healthcare access, and while there are no magic bullets to healthcare reform, this study highlights that HB 2454—a Goldwater Institute landmark law that made telehealth flexibilities permanent post-COVID—is expanding healthcare services to some of the most vulnerable and under-resourced populations in the Phoenix area.

Main Findings:

Even after the pandemic, this study confirmed that more than 1 in 5 Phoenix area households are utilizing telehealth, and usage is even higher among the aging population, women, lower-income brackets, Black communities, and those who are more likely to report depression and difficulties with physical mobility.

Women’s Health

Women have been shown to be more likely than men to utilize in-person healthcare, and this study along with other national findings confirms they are more likely to use telehealth as well. This study found that 1 in 4 women reported utilizing telehealth within the last month.

Mental Health

Individuals who reported feeling depressed “nearly every day” were almost 2 times more likely to utilize telehealth within the last month compared to those who reported no depression at all.

Older Adults

Among the aging population (65+) in the Phoenix metropolitan statistical area, a significant proportion reported having some kind of difficulty walking, which was the strongest predictor in the statistical model for telehealth utilization.

Economic & Racial Inequities

Telehealth may have major potential for bridging long-standing health inequities, particularly among populations in lower-income brackets and those who identify as a racial or ethnic minority group. The highest utilization was among Black females, with 31% utilizing telehealth within the last month.

Introduction

In 2021, Arizona adopted groundbreaking telehealth legislation: HB 2454, a Goldwater Institute reform that transformed the healthcare landscape by making pandemic telehealth flexibilities permanent.1 Allowing people to access healthcare from the comfort of their own home or personal location offers a wide range of benefits—including significant cost savings for patients and providers alike—by reducing the amount of travel and time taken off from work, and the number of clinical visits and emergency room admissions.2

National studies show that telehealth has significant potential to increase access and improve outcomes for medically underserved populations, such as older adults, those in rural communities and lower-income brackets, and those with mental and physical health challenges.3, 4

Despite telehealth’s successful track record and popularity, states have yet to achieve widespread adoption, even with looming national concerns such as critical physician shortages, growing aging populations, and an overall increased demand for healthcare services. It is estimated by 2030, Arizona will require more than 3,600 physicians to meet the state’s healthcare needs.5

More than three years ago, the onset of COVID-19 catalyzed the healthcare evolution from conventional in-person care to telehealth.

Goal

The goal of this report is to show the impact of allowing adults (ages 18+) to access healthcare from the comfort of their own home or personal location. The evaluation was among households in the Phoenix-Mesa-Chandler metropolitan statistical area (MSA) which consists of Maricopa and Pinal Counties and is a snapshot from July 2021 to July 2022.Need to add in Maricopa and Pinal Counties.

Methodology

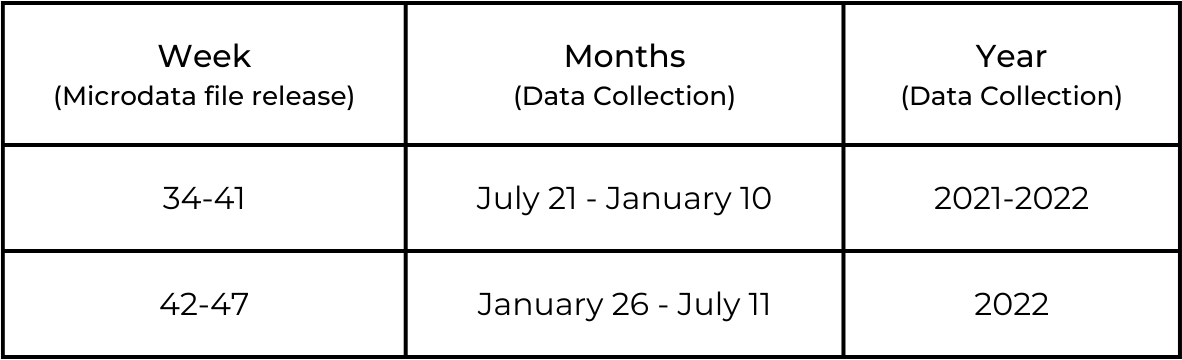

Publicly available data was obtained from the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey (HPS) microdata files (week 34 to 47, n = 17,138), which ran from July 21, 2021 to July 11, 2022.6 Responses to the telehealth variable ranged from 889 to 1,292 per week release of the microdata file. Data was weighted in SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) using the 2021 American Community Survey’s one-year estimates to correct for response bias and to be more representative of the Phoenix MSA.7 Apart from descriptives, the researcher created a prediction model using a binary logistic regression to identify which factors increase a respondent’s likelihood to utilize telehealth within the last four weeks. Variables in the prediction model include race/ethnicity, gender, age, annual household income, depression, and difficulty walking.

Table 1: Time Period of Evaluation

Explored Variables

1. Telehealth/Telemedicine Usage

HPS uses a variable that asked if the adult had an appointment with a doctor, nurse, or health professional by video or phone over the last four weeks.

2. Socioeconomic Characteristics

Characteristics that were assessed include race/ethnicity, gender, age, and annual household income.

3. Depression

The HPS uses a variable that asked how often the adult experienced feeling down, depressed, or hopeless, over the last two weeks. The outcomes were collapsed into “Not at all”, “Several Days”, & “Nearly Every Day.” This variable initially assessed a period of 1 week and changed to two.

4. Difficulty Walking

HPS uses a variable that assessed mobility and asks if the adult had difficulty walking or climbing stairs. The outcomes were collapsed into “No Difficulty,” “Some Difficulty,” and “Extreme Difficulty”.

Definitions for explored variables are derived from the HPS Data Dictionary week 47. 8

Phoenix Area Snapshot

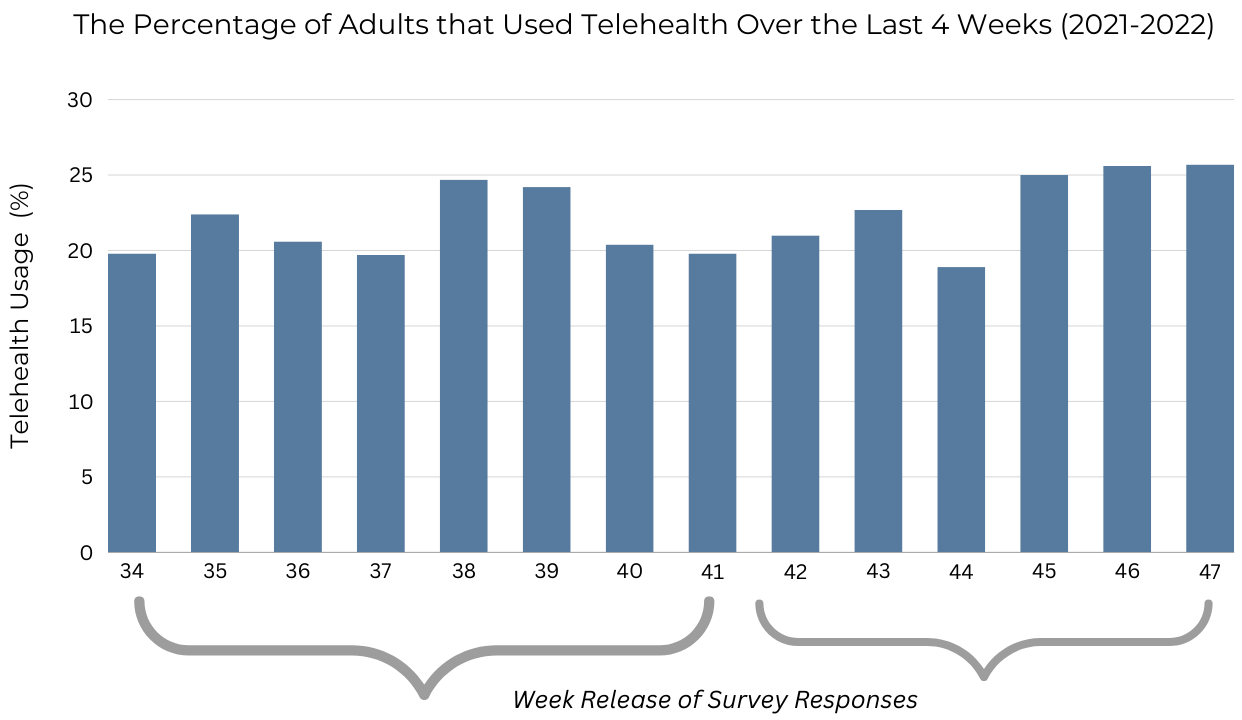

During the study period, 22.2% (CI: 21.5-23.0%) of adults ages 18 to 64 utilized telehealth over the last four weeks. Overall, usage ranged from 18.9 to 25.7% (Chart 1) but varied greatly by age, household income, race/ethnicity, gender, and those who reported having poorer physical and mental health outcomes.

More than 1 in 5 adults used telehealth

in the last 4 weeks.

Chart 1

*Represents adults ages 18-64 years.

Which populations in the Phoenix MSA were more likely to use telehealth over the last four weeks?

- The strongest predictors for telehealth usage were those who reported difficulty walking, depression, older age, and female gender.

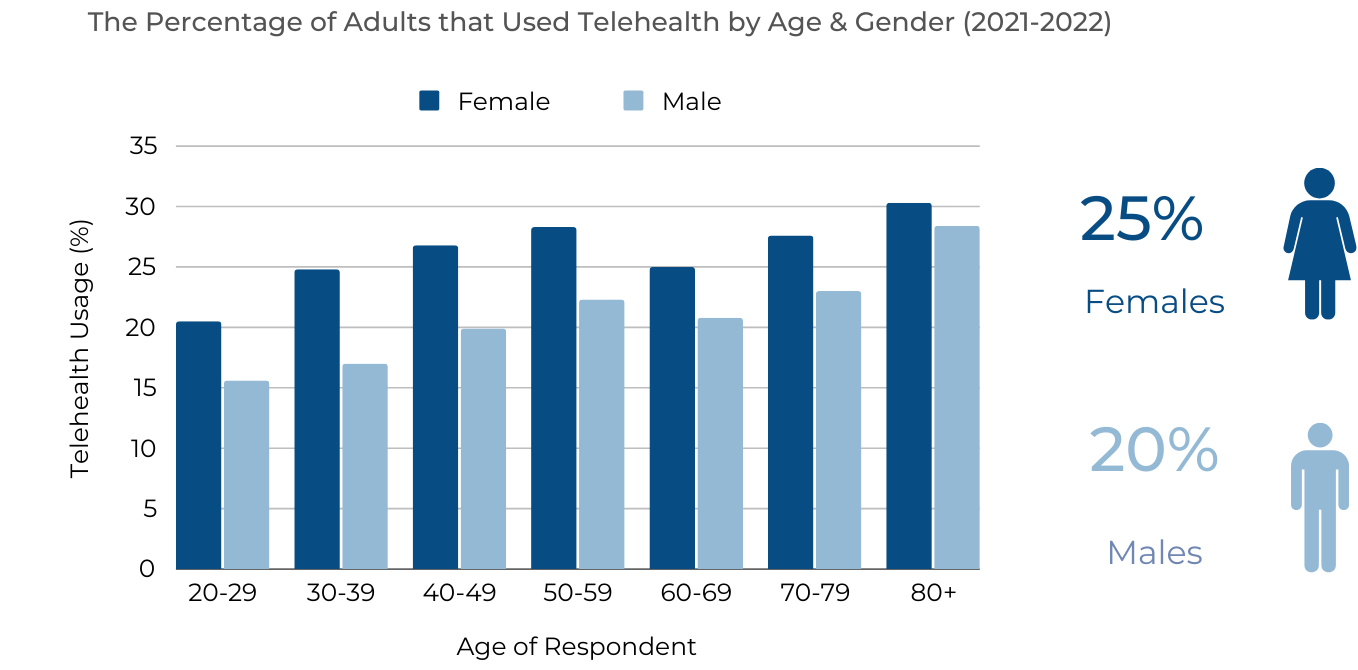

- Compared to adults (ages 20-29), adults (80+) were almost twice as likely to utilize telehealth (OR: 1.92 CI: 1.43-2.57, p < .001).

- Compared to males, females were 32% more likely to utilize telehealth (OR: 1.32 CI: 1.21-1.43, p < .001).

- Black adults were 53% more likely than White (Not Hispanic) to utilize telehealth (OR: 1.53, CI: 1.28-1.83, p < .001).

* The odds ratios (OR) for difficulty walking and depression are on page 9.

Differences by Gender, Age, & Race

Females had the highest utilization across all age groups. Highest utilization for both genders was among those aged 80 years and older (females = 30%, males = 28%).

Chart 2

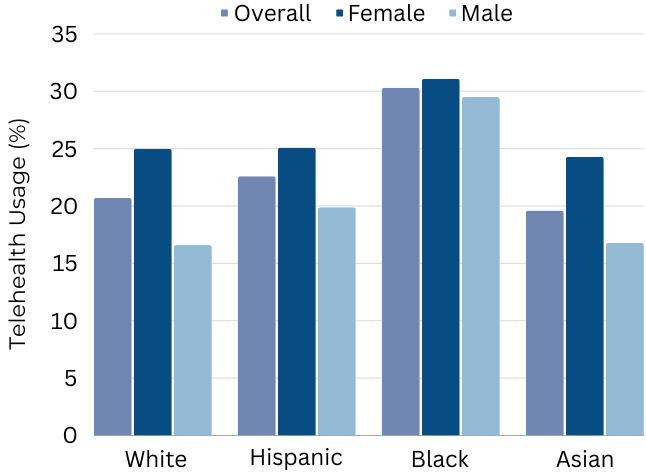

Race/Ethnicity Findings

Overall, Black adults had the highest utilization of telehealth (30.3%) followed by Hispanic (22.6%). Asian respondents had the lowest utilization (19.6%). When comparing genders, Black female respondents had highest utilization (31%) followed by Hispanic and White, which had similar usage (~25%). Among males, the groups with highest utilization include Black (29.5%) followed by Hispanic (~20%). Unlike other race/ethnicity groups who had a large gap in usage between genders, Black males and females had similar utilization in telehealth.

Chart 3

31%

Black females had the highest proportion

that used telehealth.

Socioeconomic Characteristics

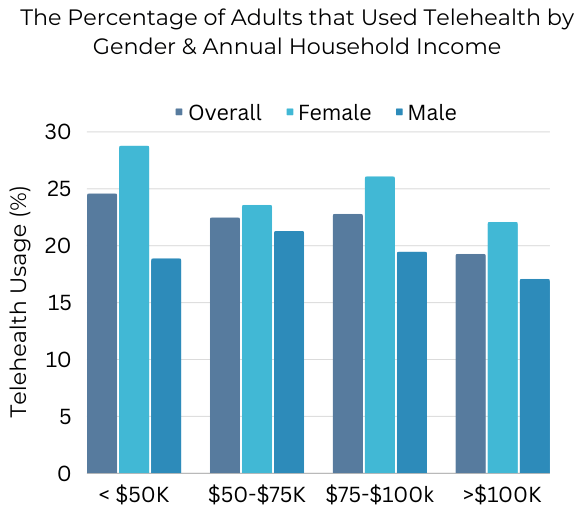

Variation by Household Income & Gender

Overall, those who had an annual household income of less than $50K per year had the highest utilization of telehealth within the last month (~25%) versus those in the highest-income bracket (19%). Females in the lowest-income bracket had the highest utilization (28.8%). For males, the highest usage was among those who had an annual household income of $50-75K (21.3%).

Chart 4

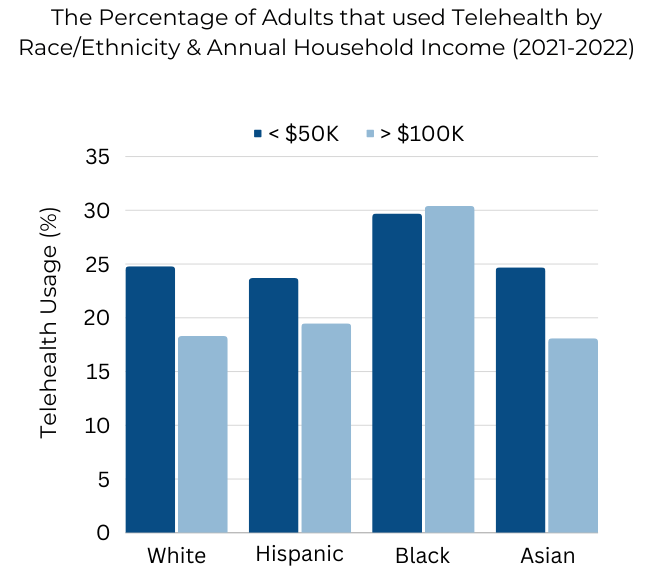

Variation by Household Income & Race

Apart from Black respondents, all race/ethnicity groups in the lowest-income bracket had the highest utilization of telehealth. For Black respondents, telehealth utilization was similar between the two annual household income brackets (~30%). Among White, Hispanic, and Asian respondents with a household income greater than $100K, less than 20% utilized telehealth within the last month. Lowest utilization was among Asian and White respondents in the highest-income category.

Chart 5

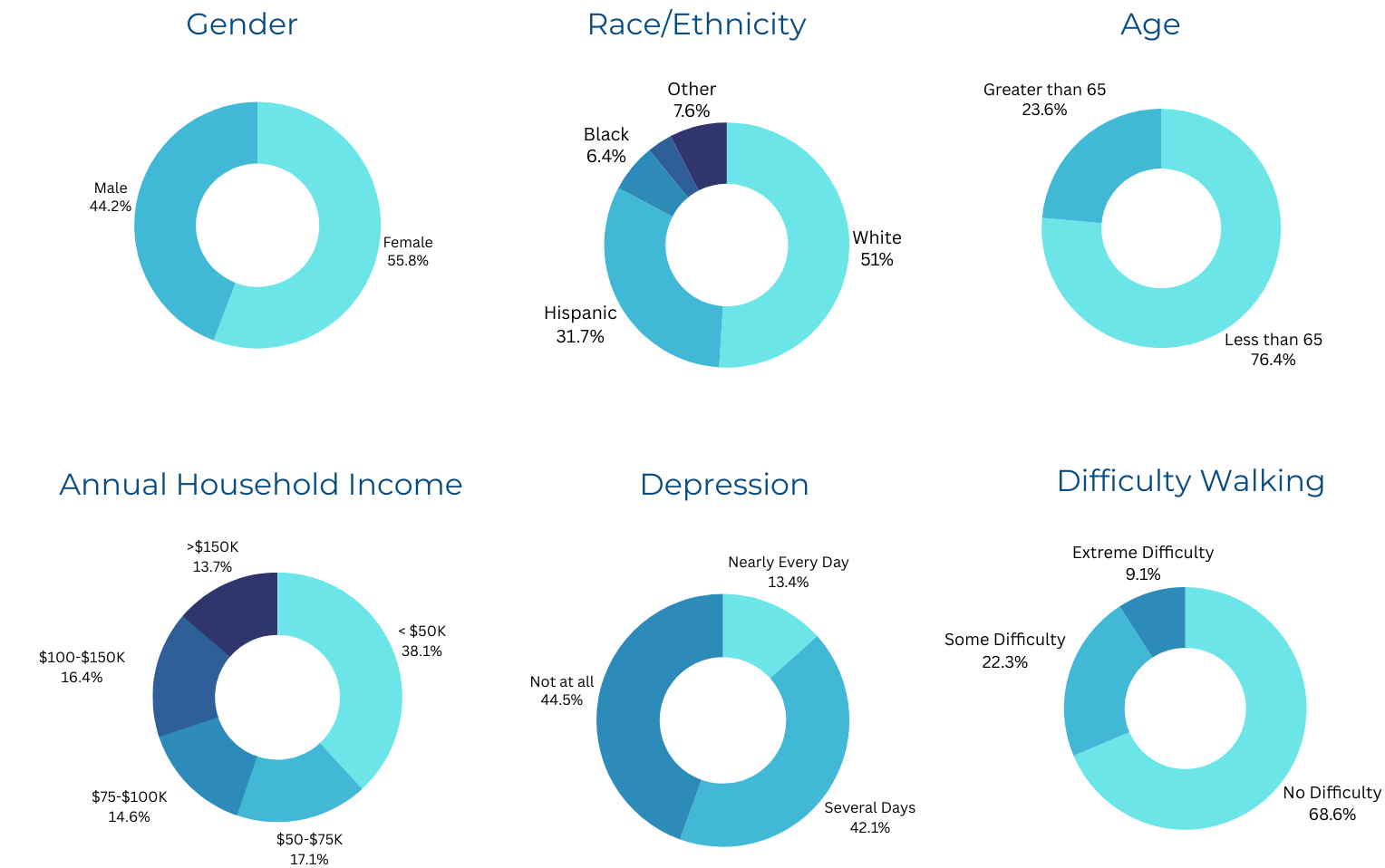

Characteristics of Adults Who Used Telehealth (18+)

The populations who used telehealth within the last four weeks had higher proportions of respondents who were female, 5 of 10 were from racial and ethnic minority groups, and almost 40% had an annual household income of less than $50K.

56% of telehealth users experienced depression.

22% of telehealth users had some difficulty walking.

Mental & Physical Health Outcomes

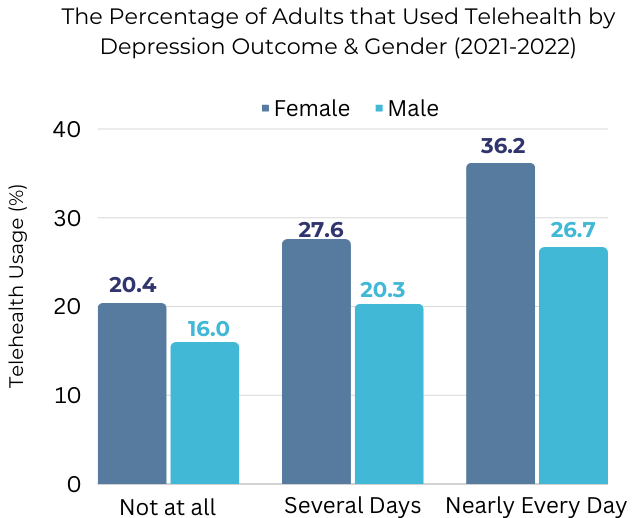

Depression

Depression was one of the strongest predictors for telehealth usage. Adults that reported feeling depressed “nearly every day” were almost two times more likely (OR: 1.92, CI: 1.67 – 2.20) to use telehealth than those who reported experiencing depression “not at all.”

Females and males who said they experienced depression nearly every day had the highest utilization of telehealth within the last month. Among females reporting near-daily depression, 36% had used telehealth within the last four weeks compared to those who reported no depression at all (20.4%).

Chart 6

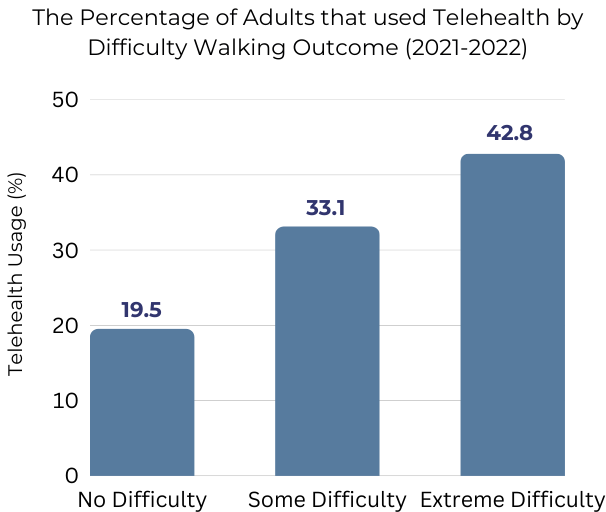

Difficulty Walking

The strongest predictor in the statistical model for telehealth usage was the variable that assessed difficulty walking. Respondents that reported having extreme difficulty walking were 2.3 (OR: 2.30, CI: 1.95 – 2.73) times more likely to utilize telehealth than those who did not report any difficulty walking. More than 40% of respondents who reported extreme difficulty with walking used telehealth within the last month compared to 19.5% of those who reported having no difficulty.

Chart 7

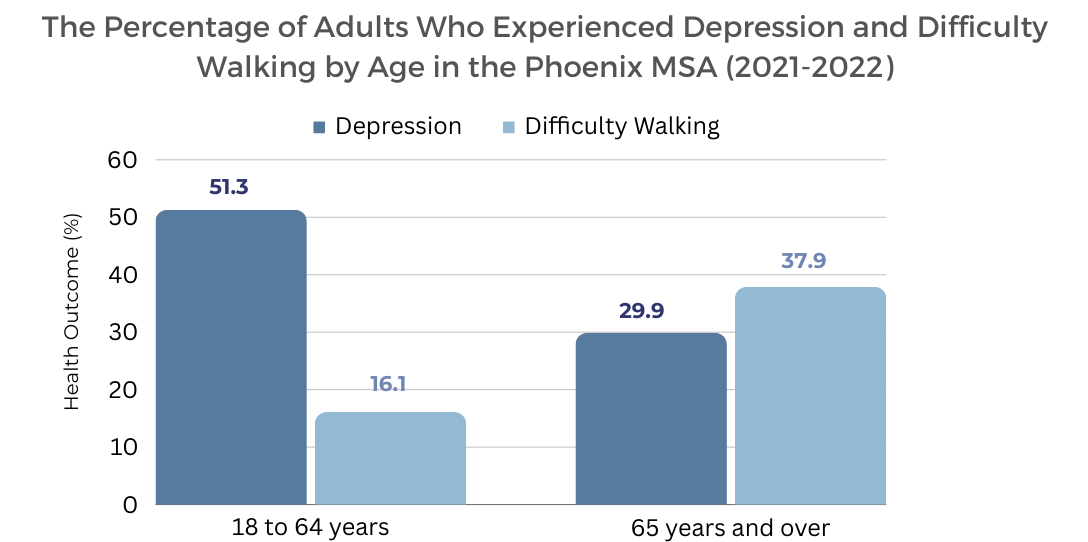

Mental & Physical Health Outcomes in the Phoenix MSA

Difficulty walking and depression varied significantly by age (Chart 8). Adults younger than 65 years were more likely to report feeling some kind of depression compared to their older counterparts. However, the aging population still faced poor mental health challenges and had a higher proportion of respondents who reported difficulty walking. Among those who were 65 years or older and resided in the Phoenix MSA, approximately 38% reported difficulty walking, and it was even more pronounced among those who utilized telehealth within the last month.

Chart 8

Telehealth users 65+:

5/10 had difficulty walking.

4/10 had depression.

Overview of Results

Overall, more than 1 in 5 respondents younger than 65 years reported using telehealth within the last four weeks during the study period of July 2021 to July 2022, with significant differences in utilization by gender, age, race/ethnicity, income, and physical and mental health outcomes. Females had higher usage across all age groups (25%) compared to their male counterparts (20%).

Black females (31%) had the highest utilization followed by Black males (29.5%). Annual household income appeared to play a role in telehealth utilization for most race/ethnicity groups. Those who identified as White (Not Hispanic), Hispanic, or Asian and were in the lowest-income bracket had the highest utilization compared to their counterparts that made greater than $100K per year.

Poor mental and physical health outcomes were magnified among those who used telehealth. Among respondents younger than 65 who utilized telehealth, more than half reported experiencing some kind of depression. Among females who reported feeling depression nearly every day, 36% utilized telehealth compared to those who reported not feeling depressed at all (20%). Poor functional mobility, like difficulty walking, was significantly higher among those who utilized telehealth and those who were older.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that even after the pandemic, a significant proportion of the Phoenix MSA is utilizing telehealth, and it may play a critical role for populations who historically have had decreased access to care, such as the aging population, lower-income households, Black and Hispanic communities, and those who are more likely to report depression and difficulty walking.

Women’s Health

Women have been shown to be more likely than men to utilize in-person healthcare, and this study along with other national findings confirms they are also more likely to use telehealth.9 Women, who historically have been caregivers for families and loved ones, may account for higher utilization of telehealth due to convenience and time savings. Whether for aging parents, their partners, or children, women have been shown to be the main decision makers for their families’ healthcare.10 Other reasons for increased utilization are women’s health needs across a lifespan, which may include prenatal care, primary care, menopause health, and consultations for gynecology.

A study conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation in 2020, found that 6 in 10 women ages 50-64 had a chronic condition that needs to be monitored regularly.

Apart from healthcare needs, several studies have revealed social reasons (i.e., mistrust, stigma, and gender norms) that men are less likely than women to receive preventative check-ups, mental health treatment, and other types of medical services.12,13,14 Telehealth could bridge this gap and play a major role in addressing both genders and their specific constructs, perceptions, and barriers to care.

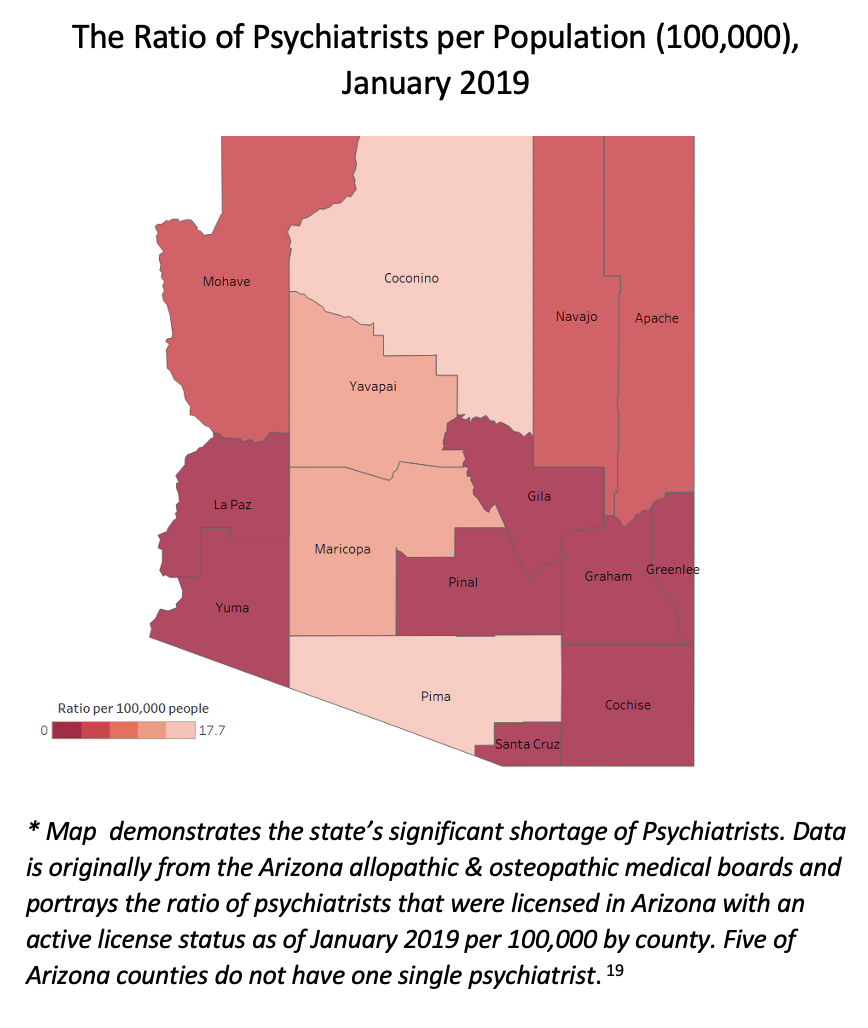

Mental Health

Depression was the second-strongest predictor in the statistical model for telehealth utilization, which demonstrates its potential to do the following: 1) improve the shortage of mental healthcare providers, 2) increase access for people in rural areas, 3) decrease the stigma by removing in-person care, 4) lower emergency room (ER) visits, and 5) address some of the devastating consequences related to mental illness, such as homelessness, overdoses, and suicide.15, 16 An analysis of outpatient/office visit claims in 2021 showed that “Psychiatry and Substance Use Disorder Treatment” had the highest telehealth penetration compared to all other healthcare specialties.17

In 2022, the National Center for Health Statistics showed that 35% of Arizonans experienced anxiety or depressive disorder. This analysis did not assess disorders, but it did show that a significant proportion of Phoenix MSA households are experiencing some kind of depression – whether for a few days a week or every day. In places like Arizona, which ranks 47th out of 50 states for the rate of available mental healthcare providers, it is critical to get buy-in from multiple stakeholders to ensure widespread adoption of telepsychiatry, addiction counseling, and other tele-mental healthcare services across the state.18

Aging Population & Rural Areas

Among the aging population in the Phoenix MSA, a significant proportion reported having some degree of difficulty walking, which was the strongest predictor in the statistical model for telehealth utilization. Studies have shown that older adults experience more problems with walking due to balance and dizziness, which can be caused by medication, chronic disease, and other medical conditions.20 The U.S. Census Bureau has predicted that by 2035, older adults will outnumber children, and telehealth may play a critical role in allowing older individuals to age in place, permitting them to stay in the comfort of their own home environment at a lower cost to families and taxpayers.21

Approximately, 15% of the Phoenix MSA is 65+, however, rural areas in Arizona have significantly higher proportions of people in this age bracket—including La Paz, Yavapai, and Mohave counties, where more than 30% of their population is 65 or older.22 Apart from their aging demographic, rural areas have significantly poorer health outcomes and poorer healthcare infrastructure, which makes telehealth adoption, health information technology, and digital literacy important issues to address.23

Economic & Racial Inequities

During the pandemic, several research studies found telehealth’s potential for bridging long-standing health inequities, particularly among some populations in lower-income brackets and those who identify as Black and Hispanic. Some researchers hypothesize that telehealth makes it easier to bring care to where the patient is located, which has major benefits for communities that may mistrust in-person care or have transportation barriers or difficulty taking time off from work.24

Studies have shown that chronic disease and poorer health outcomes that require more frequent healthcare visits are magnified among populations of lower socioeconomic status.25 A survey conducted in 2020 showed that among women on Medicaid, approximately 3 of 10 had a disability or a chronic disease.26 Telehealth overcomes one of the most significant obstacles for these populations, which is transportation—or just gaining entry into the healthcare system. Some of the most frequently cited barriers for transportation are lack of availability, far travel distance, and cost.27

Conclusion

Despite COVID-19 being a period most Americans will never forget, it did reveal many long-standing weaknesses in the nation’s healthcare system and catalyzed the emergence of telehealth, which removed the geographic, financial, and physical barriers that can be associated with in-person care. This analysis highlights that more than 1 in 5 respondents are accessing healthcare from the comfort of their own homes, and utilization was even higher among Phoenix-area communities who may be under resourced and have challenges associated with aging, poverty, mental health, and physical mobility.

Overall, there is no better way to improve health outcomes and holistically address accessibility than by bringing care to where the individual is located. More states and lawmakers need to follow Arizona’s lead and make telehealth flexibilities that were once temporary 100% permanent.

Moving Forward

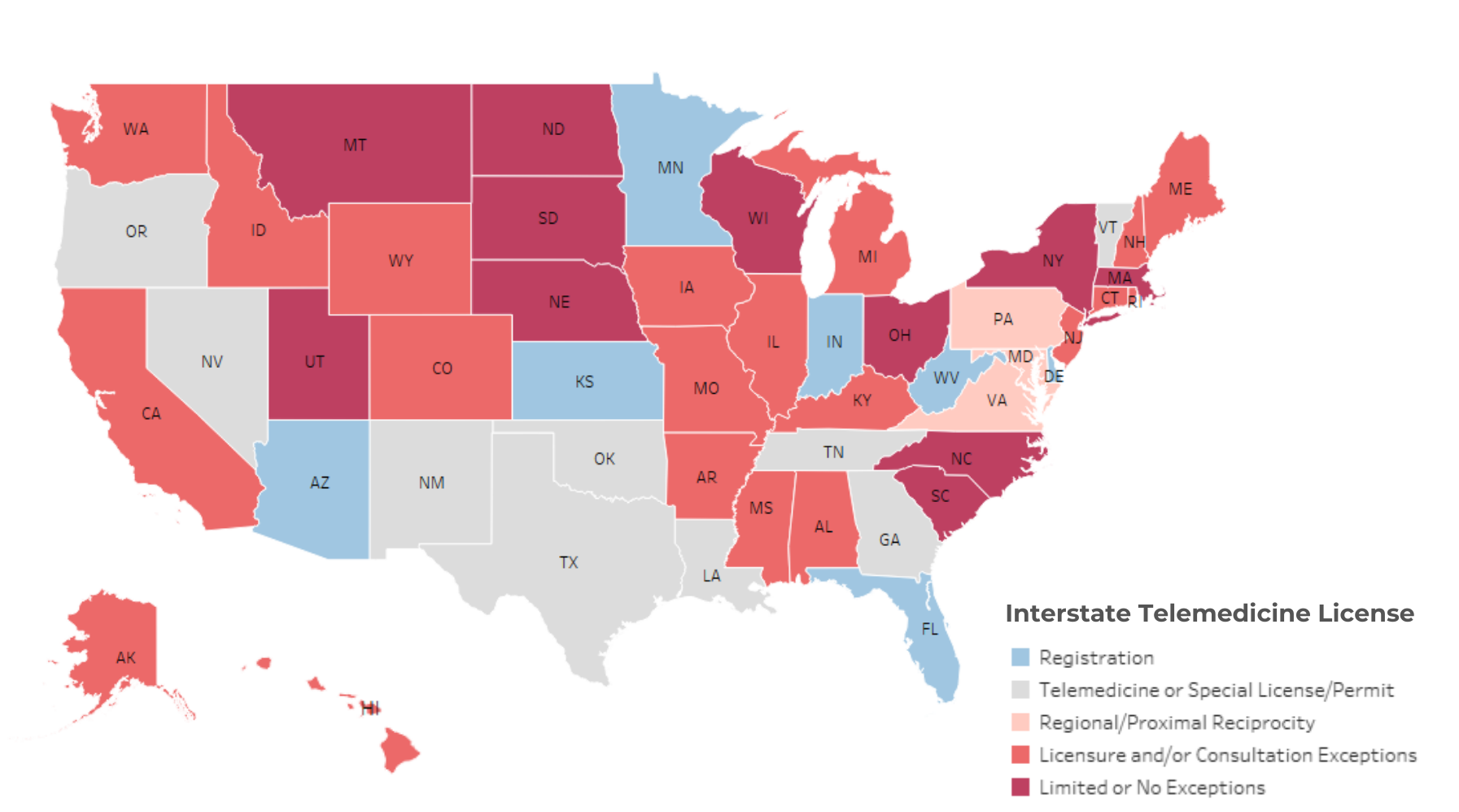

Significant demographic changes coupled with looming physician shortages require policymakers and health systems to open the door to innovation and 21st century healthcare. While some states have recognized the groundbreaking potential of telehealth flexibilities and created permanent reforms, a significant number of states have sadly closed this door and made only minor adjustments to their laws.28

HB 2454 guaranteed Arizona interstate telehealth – or the ability for OOS (out-of-state) providers to practice telehealth without having to jump through hoops and obtain an in-state license.

Some states have identified policies that are low hanging fruit—like interstate telemedicine, which allows patients to access providers outside their state. Unfortunately, too many states and medical boards require an in-state license for OOS providers to practice telemedicine or have a burdensome application process forcing providers to jump through time-consuming or expensive hoops.29, 30 The American Medical Association estimates the minimum wait time to obtain a license in another state is at least 60 days.31

Apart from a few exceptions, more than 60% of states require OOS healthcare providers to be fully licensed in their state to practice telemedicine while only a handful of states along with Arizona have a registration process that completely removes this barrier. Yet allowing providers to easily practice across state lines can improve accessibility, appointment wait times, the number of specialty providers, and the diversity of doctors which may be more representative of the populations they serve.32, 33

Interstate Telemedicine License by State (Jan. 2024)

* Data obtained from the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) and the Center for Connected Health Policy, January 28th, 2024.34, 35 This map does not account for states that may have multiple exceptions and/or mechanisms to practice interstate telemedicine. Please refer to the FSMB for more detailed information.

Definitions for Map:

Registration (7) : This process allows OOS physicians and/or other healthcare providers to offer telemedicine services without an in-state license if they are properly registered with the state.

Telemedicine or Special License/Permit (9): Allows providers to practice without an in-state license but typically requires an application process which can be burdensome. Included Vermont in this count which has a process for registration and a special license/permit.

Regional/Proximal Reciprocity (3 + DC): Full-state licensure required except for OOS providers that are in certain bordering states/jurisdictions.

Licensure/Consultation Exceptions (20): Full-state licensure required apart from some exceptions (ex: consultations, services for a limited number of days, life threatening diagnosis, etc…). Despite having a registration process, Maine was included in this count due to a requirement of consultative services only.

Limited or No Exceptions (11): Full-state license required with limited or no exceptions. Included Utah in this count which makes an exception for pro-bono care.

* End note

Telemedicine vs. telehealth – The map above uses the term telemedicine despite some states like Arizona that implement telehealth, meaning a broader range of healthcare services. Definitions are below:

Telemedicine uses telecommunications technologies to support the delivery of all kinds of medical, diagnostic, and treatment-related services, usually by doctors.

Telehealth is similar to telemedicine but is a broader definition that includes a wider variety of remote healthcare services beyond the doctor-patient relationship(i.e., nurses, pharmacists, and social workers).

Limitations

The Household Pulse Survey allows for timely evaluation of emerging public health issues, but like many surveys, it is subject to response-bias and low-response rates. The researcher took precautions and weighted the data to address response bias and ensure better representation of the Phoenix MSA. Despite improvement, response bias is still a key limitation due to the fact that 1) certain populations are more likely to respond than others and 2) individuals who are more tech savvy or have internet may be likelier to respond to this internet-based survey. Care should be taken when interpreting HPS data particularly for populations with smaller denominators or those who may have less representation in the sample.

It should be noted that HPS data has notably lower telehealth utilization compared to datasets that used a telehealth variable with a longer reference period. For example, the 2021 National Health Interview Survey asked respondents if they utilized telehealth within the last year vs. this tool, which asked if they used telehealth within the last four weeks. This shorter reference period could either underestimate telehealth utilization or offer a better understanding of what usage looks like on a more frequent basis.

Variable availability significantly impacted this evaluation. The variable that assessed telehealth utilization was not collected following week 47 which determined the time period for this analysis. Furthermore, the HPS dataset had limited options to assess race/ethnicity and rural households. For example, there was no data to assess indigenous communities, despite Arizona being home to 21 federally recognized nations, communities, and tribes. Also, the geographic variable only assessed Phoenix MSA and general non-MSA, limiting deeper exploration of trends in rural areas.

The variable that assessed annual household income had some shortcomings and was purely for explorative analysis. Despite seeing differences in telehealth utilization by annual household income, this variable did not have strong significance in the statistical model. The researcher feels the trends in telehealth utilization by annual household income may be more pronounced if the researcher adjusted the income calculation by accounting for household size.

Even though depression was a strong predictor for telehealth utilization, this analysis cannot conclude individuals who were depressed were using telehealth to access telepsychiatry, counseling, or some type of mental healthcare service. In fact, people with poorer health outcomes could be more likely to be depressed or use healthcare overall. However, even though we cannot assume a causation, this analysis does show that a significant proportion of individuals who experienced depression are in fact also utilizing telehealth, highlighting the important role telehealth could play in expanding accessibility within this arena.

Overall, the trends in this report are very similar to a national analysis that was conducted on the HPS data in 2021.36Unlike the national analysis, this evaluation was on the Phoenix MSA alone and did not evaluate the differences between audio and video, which can impact findings of telehealth utilization among certain groups, particularly among populations who are less likely to have video-enabled devices and broadband internet access.

End Notes

[1] Arizona House Bill 2454, https://www.azleg.gov/legtext/55leg/1R/laws/0320.pdf.

[2] Mahtta, Dhruv, et al. “Promise and Perils of Telehealth in the Current Era.” Current Cardiology Reports, vol. 23, No. 9, 2021, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34269884/.

[3] Mahtta, et al, “Promise and Perils of Telehealth in the Current Era.”

[4] Karimi, Madjid, et al. “National Survey Trends in Telehealth Use in 2021: Disparities in Utilization and Audio vs. Video Services.” Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, February 2022, https://www.aspe.hhs.gov/reports/hps-analysis-telehealth-use-202.

[5] Kelly, Thomas. “Banner Health & UArizona College of Medicine – Phoenix Partner to Increase Residency and Fellowship Programs.” University of Arizona College of Medicine Phoenix Newsroom, June 2023, https://phoenixmed.arizona.edu/news/gme-expansion.

[6] Based on data from The United States Census Bureau, Household Pulse Survey, data through July 2022, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey.html.

[7] Based on data from The U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 1-year estimates, data through December 2021, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/.

[8] U.S. Census, Household Pulse Survey.

[9] Lucas, Jacqueline, and Villarroel, Maria. “Telemedicine Use Among Adults: United States 2021.” NCHS Data Brief, vol. 445, October 2022, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36255940/.

[10] Goodman, Shaina, and Mackay, Erin. “Delivering on the Promise of Telehealth. How to Advance Health Care Access and Equity for Women.” National Partnership for Women and Families, March 2021, https://nationalpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/delivering-promise-telehealth.pdf.

[11] Long, Michelle, et al. “Women’s Health Care Utilization and Costs: Findings from the 2020 KFF Women’s Health Survey.” Kaiser Family Foundation, April 2021, www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/womens-health-care-utilization-and-costs-findings-from-the-2020-kff-womens-health-survey/.

[12] Bertakis, K D, et al. “Gender Differences in the Utilization of Health Care Services.” The Journal of Family Practice, vol. 49, no. 2, 2000, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10718692/.

[13] Himmelstein, Mary S, and Diana T Sanchez. “Masculinity Impediments: Internalized Masculinity Contributes to Healthcare Avoidance in Men and Women.” Journal of Health Psychology, vol. 21, no. 7, 2016, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25293967/.

[14] Chatmon, Benita N. “Males and Mental Health Stigma.” American Journal of Men’s Health, vol. 14, no. 4, 2020, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7444121/.

[15] Telehealth for the Treatment of Serious Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorders. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 2021, https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/pep21-06-02-001.pdf.

[16] “Why Telehealth Is So Important for Mental Health.” International Board of Credentialing and Continuing Education Standards, September 2022, https://ibcces.org/blog/2020/09/04/telehealth-important-mental-health/.

[17] Bestsenny, Oleg, et al. “Telehealth: A Quarter-trillion-dollar Post-COVID-19 Reality?” McKinsey & Company, July 2021, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare/our-insights/telehealth-a-quarter-trillion-dollar-post-covid-19-reality.

[18] Koch, Bryan, et al. “The Arizona Behavioral Health Workforce.” Arizona Center for Rural Health, updated July 2021, https://crh.arizona.edu/sites/default/files/2022-03/20210702_AZ_BH_WorkforceReport_FINAL_0.pdf.

[19] Koch, “The Arizona Behavioral Health Workforce.”

[20] “Older Adults and Balance Problems.” National Institute on Aging, September 2022, https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/older-adults-and-balance-problems.

[21] Lopez, Naomi. “Unleash Technology: Maximize Telehealth’s Potential.” Don’t Wait for Washington: How States can Reform Health Care Today, edited by Brian Blase, Paragon Health Institute, 2021, pp. 88-89.

[22] Based on data from The United States Census Bureau, QuickFacts Arizona; United States, data through December 2021, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/AZ,US/BZA010221.

[23] Chen, Jie, et al. “Evaluating Telehealth Adoption and Related Barriers Among Hospitals Located in Rural and Urban Areas.” The Journal of Rural health, vol. 37, no. 4, 2020, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8202816/.

[24] Mahtta, “Promise and Perils”; Karimi, Madjid, “Trends in Telehealth.”

[25] Dhruv, Khullar, and Dave, Chokshi. “Health, Income, & Poverty; Where We Are & What Could Help.” Health Affairs, October 2018, https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20180817.901935/.

[26] Long, et al, “Women’s Health Care Utilization and Costs.”

[27] Barbosa, William, et al. “Improving Access to Care: Telemedicine Across Medical Domains.” Annual Review of Public Health, vol. 42, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090519-093711.

[28] Archambault, Josh, and Natasi, Vittorio. “State Policy Agenda for Telehealth Innovation.” Cicero Institute, updated June 2023, https://ciceroinstitute.org/research/state-policy-agenda-for-telehealth-innovation/.

[29] Archambault and Natasi, “State Policy Agenda.”

[30] “Licensing Across State lines.” Health Resources & Service Administration, updated May 2023, https://telehealth.hhs.gov/licensure/licensing-across-state-lines.

[31] “Navigating State Medical Licensure.” American Medical Association, updated February 2023, https://www.ama-assn.org/medical-residents/transition-resident-attending/navigating-state-medical-licensure.

[32] Archambault and Natasi.

[33] Harris, Julia, et. al. “What Eliminating Barriers to Interstate Telehealth Taught Us During the Pandemic.” Bipartisan Policy Center, November 2021, https://bipartisanpolicy.org/report/what-eliminating-barriers-to-interstate-telehealth-taught-us-during-the-pandemic/.

[34] Based on data from the Federation of State Medical Boards, U.S. States and Territories

Modifying Requirements for Telehealth in Response to COVID-19, updated January 2024,https://www.fsmb.org/siteassets/advocacy/pdf/states-waiving-licensure-requirements-for-telehealth-in-response-to-covid-19.pdf.

[35] Based on Data from Center for Connected Health Policy, Professional Requirements Cross State Licensing, data through January 2024, https://www.cchpca.org/topic/cross-state-licensing-professional-requirements/.

[36] Karimi, et al, “National Survey Trends in Telehealth Use in 2021: Disparities in Utilization and Audio vs. Video Services.”